Have you spared a thought for chain, lately?

Chain is really, really useful stuff. It’s as tough as the metal it’s made of, yet it’s flexible. It’s compact and can be rolled onto a drum. On the flip side, it’s expensive. That’s because it’s hard to make.

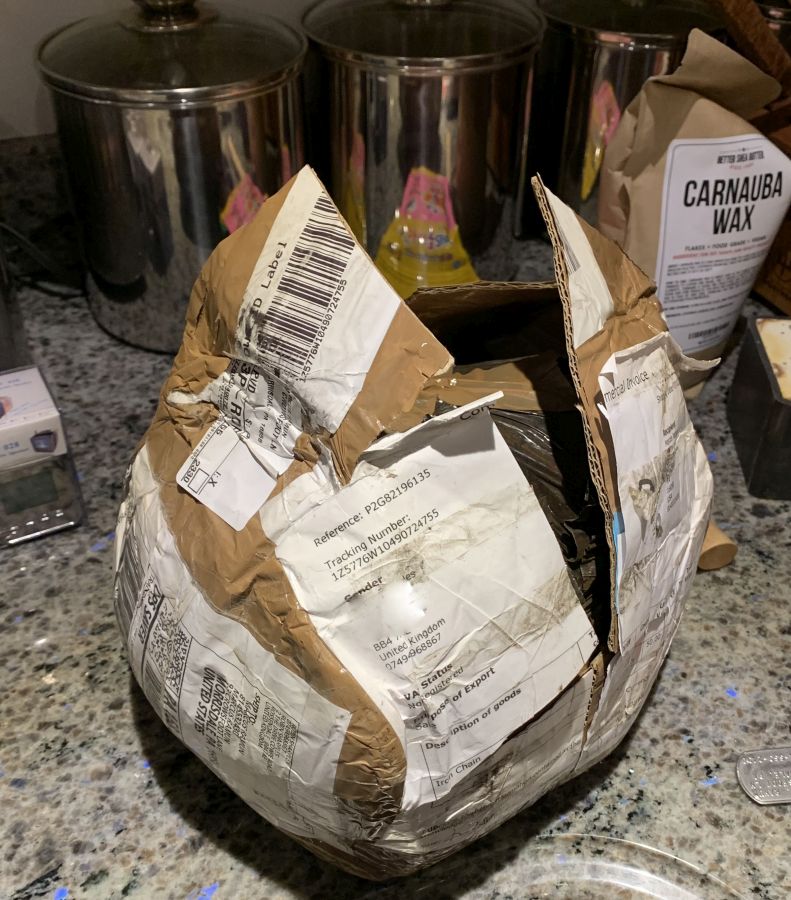

I have been thinking of chain lately because the other day, the post office called me, “come get this package, we don’t want to move it.”

When I got there, I was presented with a plastic-wrapped and heavily taped box about the size of a soccer ball. There were tattered remnants of a flat-rate shipping box around it, and a bunch of customs labels. The soccer ball-sized package weighed about 45lbs – just under the maximum weight limit for certain types of international shipping. I knew immediately what it was: most post office customers do not receive lengths of anchor chain in the mail, but I do.

When I got it home and carefully snipped the packaging away, I was presented with a lot of loose rust and, to be honest, I didn’t take any more pictures than the one of the wrapping because chain is chain is chain, right? Well, not really. This stuff is 1850s wrought iron anchor chain that is made of a particularly yummy and slaggy batch of wrought iron that I look forward to turning into various cooking implements, or perhaps a hammer or two. When I unpacked it fully, I messaged the gentleman I bought it from and told him “I got it but the wrapping was pretty shredded and I’m afraid that the chain got banged about a bit and some of the rust was scraped off in spots.” He was nonplussed by that, so I had to explicitly tell him that I was pulling his leg. I have trouble imagining what the postal service could do to a 3-foot length of anchor chain that simply being anchor chain had not already done to it.

If you haven’t seen footage of what it looks like when a ship lowers its anchor and the chain-reel system loses control, it’s really quite a thing to see; go look on youtube. As the anchor and chain pay out, the extended amount of chain’s total weight increases so the unreeling chain unreels harder and faster and pretty quickly you’re looking at a blur of steel that (as we’ve seen elsewhere) is sort of a gigantic saw. [stderr] But the true excitement comes when the chain runs out and the end whips through the room, by which time you really passionately want to be somewhere else.

The chain I got is typical: 1 1/2″ thick links with a center block to keep it from folding back in on itself. I fired up Mr Happy Dancing Bandsaw and figured out how to get one of the links locked down nicely and let it do its thing. After a while, I had a few chunks of wrought iron and (the last time I lit the old forge before I took it down) I got them to welding temperature and formed them into bars so I can – I don’t know, probably fondle them Gollum-like, crooning under my breath. Various batches of wrought iron work differently, depending on how much slag there is in them. Some will split if you hammer them, others are beautifully ductile and tough as … Well, tough as anchor chain.

The nice thing about chunks of wrought iron is that they’re patient. It’ll be there when I’m ready for it.

All of this got me thinking that someone must have made that chain. In the early industrial age, there were no great big chain-making machines that consumed steel bar-stock in one side and pushed beautifully even, welded chain out the other. This is what an early 19th-century chain-making machine looked like:

I’m not sure of the technical terms for all the things in the picture. Some of the things are swages – a swage being a shaped piece of steel that you can shape hot metal by hammering it into – and mandrels – a piece of steel you can shape metal by hammering around. There’s a cutter, in the middle. And, a sample piece of chain, naturally. When you’re talking about swages and mandrels and bending jigs, they’ve got a specific size; you can’t scale the chain links up or down with this set-up without a completely different set-up.

As my dad once said, “all work is ‘women’s work'” – toxic masculinity can kiss our collective asses, right? She shouldn’t choke up on the hammer with her thumb like that, it’ll give her repetitive stress injury, but it is easier to control. Anyhow, you can see how the little horned anvil is used to form the round. My bet is that the slits in the other anvil are to correct the bar before she curves it. The round hook is probably to hold/position the link for welding. I’ve got to say, some of those links in that pile are really beautiful work. Chain is going to be much, much, stronger if the links are welded into a continuous piece, and it appears that this (posed) photo illustrates that part of the process. I bet she was pissed that the photographer was telling her to “hold still!” while that link was cooling – you have to, um, strike while the iron is hot.

This next bit of chain-making is interesting for many reasons:

The photo appears to be heavily manipulated in the print; it looks like they may have made an internegative and printed the paper at different contrast levels, that’s why there are weird effects around the lines of the hammer and tongs. Another possibility: these old negatives were often directly manipulated by pencilling right on the negative, to add density in spots, or by erasing the negative with a bit of bleach – ferric chloride – the same stuff blacksmiths use today to etch the details in a pattern-welded blade. Once the negative is erased in a spot, you can expose the area with an internegative or just pencil the details right in. (By the way, that’s why the old 20’s “Hollywood look” is hard to achieve in-camera even with fancy AI software; photographers like Hurrell used to pencil all over their negatives to make the actresses skin have that creamy, flawless grain)

From the sparks, we can tell that they’re setting the weld on the link. The fellow in the middle appears to have just hit it with a 20-lb hammer (damn!) and the other 2 guys are holding the link in place with tongs. The guy who is reaching around with his arm in the danger zone is holding a swage on a handle – it’s a curved piece that fits on top of the spot being welded, and matches the swage they’re setting the weld on. The top swage is usually slightly tighter than the diameter of the metal, so when the hammer hits it, it applies pressure in and from the sides as well as from above. That helps set the weld. Once that’s done, the guy probably switches to a smaller hammer for a couple whacks, then they would position and weld in the center-pieces, which were usually made of cast iron.

Everything about the early industrial age involved this kind of brutal, dangerous, toxic work. Those guys have to work as a tight team, because if the hammerer misses and hits one of his co-workers, they could lose a hand pretty easily. Note also the complete lack of safety equipment: no goggles, no gloves, no aprons: you work the steel in a cotton Tshirt. I’d make appreciative comments about their toughness and bravery but it’s more likely they had no choice.

The age of automation started in the 1900s through 1920s. Tasks like chain-making were perfect targets for automation – do as much of the work as possible with a machine and let the human do the detailed fiddly parts. This machine is from the 1930s:

It’s neat to me how adjustable everything is. I suppose someone understood how each of the little set-bolts corrected the alignment and motion of the components. When factories depended on machines like this one, the engineer who kept everything working was an important resource, full of the oral history of how to adjust things.

Here’s a more modern machine:

It looks like the number of humans involved in making chain has dropped down to 1 or 2 and they’re mostly quality control and feeding the input side of the machine.

How much faster is that machine, than the 3-man process with sledgehammers and swages?

Humans have gotten better at making certain kinds of stuff. Automation is what changed the face of industrial capitalism, and the US – arguably one of the inventors of automation – clung to the old way of doing things, during the 1970s and 1980s, because automating plants was extremely expensive and it was easier and more cost effective to just squeeze the labor-pool. I don’t think there is one single industrial capitalist we can point out as being the villain, but it might be Andrew Carnegie, who specialized in driving labor costs down to move profitability up without having to actually do anything more than squeeze the workers. That addicted industrialists to the system of automating processes where it was convenient, then using automation as an excuse to further pressure labor: “you have to accept lower wages because there is less work for you now that we have chain-making machines.” The result was a drag on innovation; why innovate if you can increase your profit margin 1% by getting the union to take a 1% pay cut? Well, the problem with that scenario is that when someone comes along with both automation and cheap labor, you can’t possibly compete against them profitably because they can under-price you from two angles at once.

One of the things that used to really blow my mind when I was a teenage was the suits of chainmail in museums where, if you look closely, you can see that the rings are welded. That’s the good stuff. Cheap chainmail, the rings were drilled, lapped, and pinned. Like many college students, I spent a few months wandering around with a bag of rings and pliers hanging from my belt, “knitting” chainmail until I had a passable hauberk. But, like my friends’, my chainmail was not welded or pinned. It didn’t need to be – none of us were going to take a real hit from a real mace. “No, thank you.”

Morse Chain Works

Wow; great stuff!

“the engineer who kept everything working was an important resource, full of the oral history of how to adjust things”

Another truly out for the old yarn:

The plant stops running. Downtime costs. They call the old chief engineer who just retired. “Come in as a consultant. We’ll pay you pretty much anything, just get here now”.

He comes in, wanders up and down the line, tapping things and sniffing things and so on. After an hour of this, he takes a piece of chalk from his pocket and marks a component. “Replace this”. They replace it, and the plant runs smoothly again. He submits his invoice… “Consultancy; £50,000”. They call him. “We’re not disputing the amount, but can you itemise it? You were only here an hour…?”

Comes back :

ITEMISED BILL:

Chalk Mark : £1

Knowing where to put it: £49,999

The bill was paid.

@sonofrojblake, I actually really laughed out loud, that is an excellent joke. In reality, the company’s owners would rather pay a bunch of MBA consultants who would recommend to lay off the workers and sell the manufacturing line for spare parts rather than pay someone actually competent who could save it, but even so…

My great grandfather was the engineer maintaining the steam pumping engine at a tin mine in Cornwall, which is not at all the same as being a miner despite what my kid brother likes to claim. He did it while also running a farm, as it wasn’t a full time job.

—

And my nephew is the guy in the joke, except that he does it with technology, on the largest of machines – oil rigs, furnaces, the pumping systems for moving gas across a continent scale – “yes you can run that for another six months” or “Fuck no, start shutting down now before the [thing that will mean you have to replace the whole machine rather than just that part] fails”. He’s getting a lot of guitar practise in at the moment, as of course he has to quarantine when he goes to another country before he can get to work.

It’s the no gloves that gets me. Imagine the radient heat coming off that chain link, and the little bits of flying slag. Their hands would be cooked

@dangerousbeans: those flying sparks of flux or slag go right through clothes and stick to skin. You have to dig them out with tweezers. I can’t imagine what it feels like getting hit in the eye with a spark. Nopeitty nope de nope.

Marcus,

Sorry for the off-topic question, but I was looking for any thoughts you might have on the current security hack in the federal government.

Cheers,

Jeff Hess

Have Coffee Will Write

“When factories depended on machines like this one, the engineer who kept everything working was an important resource, full of the oral history of how to adjust things.”

I expect they were also smart enough to never ever tell anyone much more than “You’ve got to set it juuust right or it’ll foul up the machine or the workpieces, and that’ll be expensive and hard to fix.”

Actually, after these and some other videos I’m wondering how you prime those chain machines. Once you have a length of chain that runs the length of the machine and passes through every station, no problem. But what if you’re just starting starting out with e.g. a fresh coil of wire? Wouldn’t it still have to thread through all the different stations (work steps) so the eventual chain will pass through them as well? Surely every part of the machine is tightl toleranced and only works if it is fed with something that looks exactly as a chain would at that stage. If you put something else in I’d expect to see some randomly bent metal and maybe some breakage. Plus, the machines are cleary pulling material, not pushing it, so again material has to reach all the way to the end through the machine to actually work.

hyphenman@#7:

Sorry for the off-topic question, but I was looking for any thoughts you might have on the current security hack in the federal government.

I will. I have been mostly /facepalming so hard that I haven’t wanted to share any of my perspective. Primal screams of frustration are not a good look.

komarov@#9:

I’m wondering how you prime those chain machines. Once you have a length of chain that runs the length of the machine and passes through every station, no problem. But what if you’re just starting starting out with e.g. a fresh coil of wire?

That is a GREAT question. The answer (as I understand it) is that many times these production lines are designed to never restart. If you shut it down that’s OK but you may have to do something that re-heats a particular stage or whatever. If a piece of chain, say, breaks, then you have to manually tie a link to the earlier piece using a split link so it’ll draw.

I had a conversation once with a guy at Corning glass (this was regarding cybersecurity) and he said that they keep some production lines running always because if they shut down the glass in the machines will congeal and then it takes a month for someone to chisel out all the congealed glass- it’s cheaper to keep the machine running and if there’s too much product you throw it back in the recycling.

I suspect it’s the same thing – that machine never is in a condition where there is no chain in it at all.