I stumbled on this back when the “news” first broke and concluded it was a “wait and see” kind of thing. I’m still waiting and I still haven’t seen. Allegedly someone bought one of William Shakespeare’s books on Ebay for $400.

Whose notes? (source)

Some aspects of the story sound suspicious – extremely so – to me: namely, “the lack of evidence is evidence that it’s real.” That’s a bizzare argument, especially since the book was sold on Ebay without the seller saying or thinking it belonged to Shakespeare; that conclusion was reached by the buyer, a bibliophile antiquarian, later. So, the argument appears to rest on that some of the words picked out are words Shakespeare liked and the handwriting may resemble his.

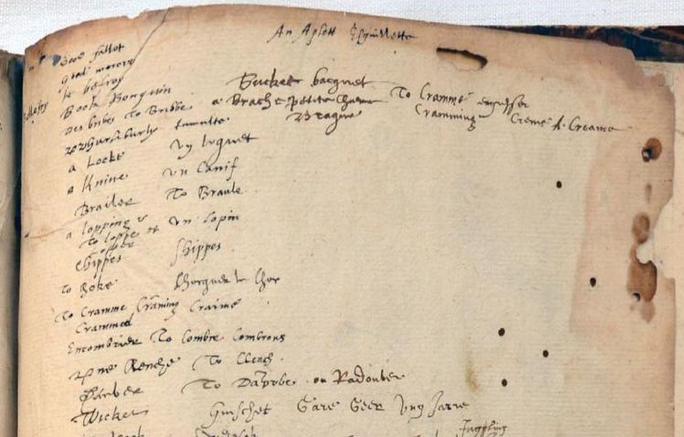

Now two antiquarian booksellers say they’ve discovered Shakespeare’s own copy of the Alvearie, annotated by the Bard himself — and they found it on eBay. To support their claim, the booksellers put the entire thing up online, pointing out numerous marginal annotations that highlight unusual words Shakespeare used in his writing. Also, whoever owned the book seems to have had a thing for the letters “W” and “S,” which appear repeatedly in fancy script in the margins.

Daniel Wechsler is one of the book’s owners. He tells Kurt the evidence pointing to Shakespeare built up gradually as he went through the annotations one by one. But on the blank back page, he and his partner found a dense “word salad” — a mixture of French and English words, some of which ended up in plays like Henry IV, The Merry Wives of Windsor, and Henry V. “If there was a smoking gun, it was this trailing blank [page],” he says.

When one buys a book with marginalia is it usually done to investigate who owned it and whose marks they may be?

The Folger Library has the canonical response:

At this point, we as individual scholars feel that it is premature to join Koppelman and Wechsler in what they have described as their “leap of faith.” Having ourselves worked extensively with collection materials and digital corpora, we have written this blog post in order to highlight research methods that we expect will be used to evaluate Koppelman and Wechsler’s claims. Regardless of the identity of the annotator, the book that Koppelman and Wechsler (hereafter K&W) have turned up is fascinating. The person who annotated this copy of Baret was clearly interested in the poetic and associative possibilities of English, French, and other languages, an interest that reflects the more widespread humanist practice of “commonplacing” one’s reading. (Commonplacing refers to the practice of recording words or phrases that a reader feels can be saved for later use in composition.) The marks in this copy of the Alvearie are consistent with this collecting or “commonplacing” impulse; they could also be the marks of someone revising for another edition, adding words and cross-references to make the book more up-to-date and user-friendly.

The books’ owners have a website, too, (of course) and are offering a facsimile of the text.

I was reminded to see what had developed around this story (not much!) since it first crossed my radar screen, because I was trying to find an excellent video I stumbled across a few years ago, in which some scholars were discussing Shakespeare’s source material. I was thrilled and fascinated to learn that scholars study his material like detectives, searching for common phrases or themes that may have crept into his writing from identifiable sources. It sounds a lot like biblical textual criticism, only it’s about something actually interesting.

Literary mysteries are great fun, mostly because I find that it’s much more plausible that bibliophiles would hunt down rare books with such energy, than people who were searching for mere gold. Some of my favorites would be: Perez-Reverte’s “The Club Dumas” and Caldwell and Thomason’s “The Rule of Four” There was another I read that was a moody and atmospheric story about someone working in a bookstore who got caught up in a search for a previously undiscovered Shakespeare manuscript – but I can’t remember the title. One thing I note about most literary mysteries is that they seem to leave a teaser: it’s not reasonable to end with the protagonists discovering the great unpublished whatever, because then the reader will want to know “what did it say!?” and the author, also, doesn’t know. So when I read a literary mystery I expect to be disappointed at the end.

The Folger Shakespeare Library: Buzz or Honey, Shakespeare’s Beehive Raises Questions

Shakespeare’s Beehive (the owners of the book in question)

WNYC: They Found Shakespeare’s Dictionary on Ebay

The Atlantic: Has Shakespeare’s Own Dictionary Been Found?

I’m no expert on early modern manuscripts (heck, I hated palaeography with a passion when I had to do it for my doctorate) but I do know that it’s far from an exact science – especially when the manuscripts in question have no details of provenance to work from. Handwriting analysis and speculation on whether particular phrases or ideas might have been heard by someone of Shakespeare’s education and position can only take you so far, and as for “there were a load of words on one page that ended up in Henry V”, you could probably find several dozen early modern texts about kings and fighting that use the same set of words (Shakespeare’s plays actually display quite a limited range of vocabulary by most standards). I expect the most we’ll be able to say with any confidence is that this is definitely a late 16th / early 17th century production or definitely not from that period.

cartomancer@#1:

Me either. There’s a pretty cool description in Perez-Reverte about forging an antique document (it sounds like it’s more common than most of us would expect) Based on that, which is not much, I imagine it’d be plausible for a forger to get their hands on an old copy of a book then add shakespearean “notes” using an old carbon/oak gall ink.

Forgeries (I’m not saying this is a forgery, it may just be wishful thinking on the part of the book’s current owners) fascinate me. It requires serious scholarship to be able to forge something as well-understood as certain texts – all you’d need is one wrong word and it’d be obviously fake (reminds me of the textual criticism of Daniel’s prophecies in the bible)

It gets my heart thumping to imagine what it’d be like to suddenly find a new source of information into someone like Shakespeare’s creative process. (swoon)