Proof from Intelligence

There.

What you just did is quite unique in the history of life. The act of reading, so far as we can tell, was first done within our species. This is rather astonishing, since life has been loafing around for four billion years, and complex land-based multicellular life popped up sometime around four hundred million years ago. The odds of some other species coming up with our neat trick should be pretty high, and yet none did.

We don’t just read, though. We collect reading like crows or octopuses[34] collect shiny toys, enshrining them in large buildings called “libraries.” We then leverage them to do all sorts of stupendous things, like build telescopes or launch hunks of metal into outer space.

This fits into a greater pattern: those books, telescopes, and metal bits all exist to gather knowledge, which we then sift through in search of patterns and more knowledge. This perpetual cycle of gathering and interpreting is a sign of intelligence, something that just seems to be lacking in other animals. It’s richly rewarded us, by doubling our life span, freeing our spare time for more knowledge gathering, and building us some very cool toys.

If it’s been such a help to us, though, why haven’t other animals jumped on the intelligence bandwagon? Perhaps this is something exclusive to our species, something that took a divine touch to bring about.

Definitions

There are two ideas hidden behind this proof. Homo Sapiens Sapiens[35] has intelligence, while other species don’t, so we must be special. And since intelligence couldn’t possibly have evolved via small steps, it can only have come from god. To rebut these, I have to show that other species have some intelligence, and that there’s nothing we have that they don’t in smaller doses.

Note that I don’t have to show that other animals are smarter. The Fangtooth fish may have the longest teeth in proportion to its body size,[36] but no one would argue this proves it was blessed by a deity. In fact, we’d prefer to find a wide variety of intelligence in the animal kingdom; just like comparing other species’ eyes to infer the eye’s evolution, we can trace the development of intelligence by snooping on other intelligent beings.

But before I can show intelligence in other species, we need to get one thing straight: What is intelligence?

This may seem like a simple problem, but it has haunted philosophers and scientists for centuries. Everyone “knows” it when they see it, yet they struggle to describe it:

Individuals differ from one another in their ability to understand complex ideas, to adapt effectively to the environment, to learn from experience, to engage in various forms of reasoning, to overcome obstacles by taking thought. Although these individual differences can be substantial, they are never entirely consistent: a given person’s intellectual performance will vary on different occasions, in different domains, as judged by different criteria. Concepts of “intelligence” are attempts to clarify and organize this complex set of phenomena. Although considerable clarity has been achieved in some areas, no such conceptualization has yet answered all the important questions, and none commands universal assent. Indeed, when two dozen prominent theorists were recently asked to define intelligence, they gave two dozen, somewhat different, definitions.

(Ulric Neisser et al, “Intelligence: Knowns and Unknowns,” American Psychologist , February 1996)

And without a clear definition, there is ample wiggle room to define “intelligence” in a way that’s convenient for you. An example: I can state as a fact that I believe a god exists. This might seem impossible for an atheist:

Atheist \A"the*ist\, n. [Gr. ? without god; 'a priv. + ? god: cf. F. ath['e]iste.] 1. One who disbelieves or denies the existence of a God, or supreme intelligent Being. 2. A godless person. [Obs.] Syn: Infidel; unbeliever.

(Webster’s Dictionary, 1913 edition)

And yet there’s no conflict here. Look up “believe” in a thesaurus, and you’ll find “assume” right next to it. While both words refer to a fact that is true despite a lack of evidence, a “belief” is implied to be absolutely true, while an “assumption” is only relatively true. Assumptions can be easily discarded if proven false, and you’re free to pretend they were false if you’d like. Beliefs should remain true no matter what facts come to light, and thus should never change. Nonetheless, both meanings are close enough to be confused and interchanged, which is exactly what I did.

“God” has traditionally meant a powerful conscious being, but that definition has been expanded over the years. Pantheists reject that meaning, for instance, as well as the concept of souls. Instead, they define “god” as the entirety of the universe. Since the universe is just a definition, as per my remarks in Cosmological, that’s entirely consistent with my world-view.

So while I said

I believe that a god exists,

my true meaning was closer to

I assume that a universe exists,

which is quite compatible with atheism. The lesson is obvious: without a consistent, clear definition for “intelligence,” it’s easy to shift the meaning of the word around to suit your whim and dodge whatever argument you’re facing.

That doesn’t make it impossible to counter-argue, though. Look over the various definitions of intelligence, and you’ll note they’re usually a mix of mental attributes, such as logical thinking and tool use. By examining each potential component separately, I can check most definitions of intelligence without defining the term.

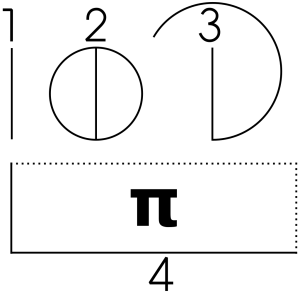

The most popular test of intelligence is the “psychometric approach,” for the simple reason that it can be easily tested. The victim is given a set of problems to work on, and asked to solve as many as possible until the clock runs out. Anything that can be fit on a sheet of paper has been on an intelligence test at some point, ranging from word vocabulary to picture patterns. Today these tests focus on abstract logic and reasoning, mathematics, and solving novel problems.

As implied, they usually split apart intelligence into several sub-components. For instance, the popular Cattell-Horn-Carroll theory uses ten categories:

- Quantitative Knowledge: In a word, mathematics.

- Short-Term Memory: The ability to remember things for a few seconds.

- Long-Term Storage and Retrieval.

- Reading/Writing: The ability to read and write, and all skills directly related to that.

- Visual Processing: Dealing with visual patterns, by analysing, remembering or creating them.

- Auditory Processing: Much like the above, though this also includes speech.

- Processing Speed: How well someone can repeat a mental task.

- Reaction Time: How quickly a person can respond to some input.

- Fluid Intelligence: Reasoning with new problems or information.

- Crystallized Intelligence: Reasoning with old problems or information, as well as the amount of information already known and the ability to share that with others.

(Most of us would group those last two categories as “problem solving,” and in the interest of keeping my workload down I’ll take full advantage.)

Other researchers have rejected easy tests of intelligence, and broadened the definition still further. Howard Gardner’s theory of multiple intelligences includes:

- Logic and Mathematics.

- Linguistic: Reading and writing, plus the ability to use speech.

- Spatial: The ability to picture and analyse a scene, be it real or a product of the mind.

- Kinesthetic: How well people can control their own bodies, including how quickly they react and memorize sequences of movement.

- Musical: Recognizing or producing a pitch or beat, and the ability to play or write music.

- Intrapersonal: How well someone knows their emotions, desires, and abilities.

- Interpersonal: The ability to interact with society, including recognizing another person’s intrapersonal content and sharing information with others.

- Naturalistic: Interacting with other species, and the ability to nurture.

I myself will add on another few categories, to catch a few other talents that have been flagged as unique to our species:

- Tool Use

- Play

- Culture

- Altruism

- Lying

- Long-term Planning

- Creativity

[34] Yes, that’s really the plural form of “octopus.” While “octopodes” is the correct Greek plural, it’s so rarely used that dictonaries either bury it as the last candidate or don’t mention it at all. “Octopi” is completely wrong.

[35] Homo Sapiens means “Wise Man;” anthropologists have begun tacking on an extra “Wise” to make room for a potential sub- or co-branch of our species, and given our messy origins I think this is a Wise idea.

[36] They’re so long that if it closed its mouth like other creatures do, its front teeth would stab through the brain and create an impressive set of horns poking out of its forehead.