Daryl Bem must be sick of those puns by now.

Back in 2011 he published Feeling the Future, a paper that combined multiple experiments on human precognition to argue it was a thing. Naturally this led to a flurry of replications, many of which riffed on his original title. I got interested via a series of blog posts I wrote that, rather surprisingly, used what he published to conclude precognition doesn’t exist.

I haven’t been Bem’s only critic, and one that’s a lot higher profile than I has extensively engaged with him both publicly and privately. In the process, they published Bem’s raw data. For months, I’ve wanted to revisit that series with this new bit of data, but I’m realising as I type this that it shouldn’t live in that Bayes 20x series. I don’t need to introduce any new statistical tools to do this analysis, for starters; all the new content here relates to the dataset itself. To make understanding that easier, I’ve taken the original Excel files and tossed them into a Google spreadsheet. I’ve re-organized the sheets in order of when the experiment was done, added some new columns for numeric analysis, and popped a few annotations in.

Odd Data

The first thing I noticed was that the experiments were not presented in the order they were actually conducted. It looks like he re-organized the studies to make a better narrative for the paper, implying he had a grand plan when in fact he was switching between experimental designs. This doesn’t affect the science, though, and while never stating the exact order Bem hints at this reordering on pages three and nine of Feeling the Future.

What may affect the science are the odd timings present within many of the datasets. As Dr. R pointed out in an earlier link, Bem combined two 50-sample studies together for the fifth experiment in his paper, and three studies of 91, 19, and 40 students for the sixth. Pasting together studies like that is a problem within frequentist statistics, due to the “stopping problem.” Stopping early is bad, because random fluctuations may blow the p-value across the “statistically significant” line when additional data would have revealed a non-significant result; but stopping too late is also bad, because p-values tend to exaggerate the evidence against the null hypothesis and the problem gets worse the more data you add.

But when pouring over the datasets, I noticed additional gaps and oddities that Dr. R missed. Each dataset has a timestamp for when subjects took the test, presumably generated by the hardware or software. These subjects were undergrad students at a college, and grad students likely administered some or all the tests. So we’d expect subject timestamps to be largely Monday to Friday affairs in a continuous block. Since these are machine generated or copy-pasted from machine-generated logs, we should see a monotonous increase.

Yet that 91 study which makes up part of the sixth study has a three-month gap after subject #50. Presumably the summer break prevented Bem from finding subjects, but what sort of study runs for a month, stops for three, then carries on for one more? On the other hand, that logic rules out all forms of replication. If the experimental parameters and procedure did not change over that time-span, either by the researcher’s hand or due to external events, there’s no reason to think the later subjects differ from the former.

Look more carefully and you see that up until subject #49 there were several subjects per day, followed by a near two-week pause until subject #50 arrived. It looks an awful like Bem was aiming for fifty subjects during that time, was content when he reached fourty-nine, then luck and/or a desire for even numbers made him add number fifty. If Bem was really aiming for at least 100 subjects, as he claimed in a footnote on page three of his paper, he could have easily added more than fifty, paused the study, and resumed in the fall semester. Most likely, he was aiming for a study of fifty subjects back then, suggesting the remaining forty-one were originally the start of a second study before later being merged.

Experiment 1, 2, 4, and 7 also show odd timestamps. Many of these can be explained by Spring Break or Thanksgiving holidays, but many also stop at round numbers. There’s also instances where some timestamps occur out-of-order or the sequence number reverses itself. This is pretty strong evidence of human tampering, though “tampering” isn’t the synonymous with “fraud;” any sufficiently large study will have mistakes, and any attempt to correct those mistakes will look like fraud. That still creates uncertainty in a dataset and necessarily lowers our trust in it.

I’ve also added stats for the individual runs, and some of them paint an interesting tale. Take experiment 2, for instance. As of the pause after subject #20, the success rate was 52.36%, but between subject #20 and #100 it was instead 51.04%. The remaining 50 subjects had a success rate of 52.39%, bringing the total rate up to 51.67%. Why did I place a division between those first hundred and last fifty? There’s no time-stamp gap there, and no sign of a parameter shift. Nonetheless, if we look at page five and six of the paper, we find:

For the first 100 sessions, the flashed positive and negative pictures were independently selected and sequenced randomly. For the subsequent 50 sessions, the negative pictures were put into a fixed sequence, ranging from those that had been successfully avoided most frequently during the first 100 sessions to those that had been avoided least frequently. If the participant selected the target, the positive picture was flashed subliminally as before, but the unexposed negative picture was retained for the next trial; if the participant selected the nontarget, the negative picture was flashed and the next positive and negative pictures in the queue were used for the next trial. In other words, no picture was exposed more than once, but a successfully avoided negative picture was retained over trials until it was eventually invoked by the participant and exposed subliminally. The working hypothesis behind this variation in the study was that the psi effect might be stronger if the most successfully avoided negative stimuli were used repeatedly until they were eventually invoked.

So precisely when Bem hit a round number and found the signal strength was getting weaker, he tweaked the parameters of the experiment? That’s sketchy, especially if he peeked at the data during the pause at subject #20. If he didn’t, the parameter tweak is easier to justify, as he’d already hit his goal of 100 subjects and had time left in the semester to experiment. Combining both experimental runs would still be a no-no, though.

Uncontrolled Controls

Bem’s inconsistent use of controls was present in the paper, but it’s a lot more obvious in the dataset. In experiments 2, 3, 4, and 7 there is no control group at all. That is dangerous. If you run a control group through a protocol nearly identical to that of the experimental group, and you don’t get a null result, you’ve got good evidence that the procedure is flawed. If you don’t run a control group, you’d better be damn sure your experimental procedure has been proven reliable in prior studies, and that you’re following the procedure close enough to prevent bias.

Bem doesn’t hit that for experiments 2 and 7; the latter isn’t the replication of a prior study he’s carried out, and while the former is a replication of experiment 1 the earlier study was carried out two years before and appears to have been two separate sample runs pasted together, each with different parameters. In experiments 3 and 4, Bem’s comparing something he knows will have an effect (forward priming) with something he hopes will have an effect (retroactive priming). There’s no explicit comparison of the known-effect’s size to that found in other studies, Bem’s write-up appears to settle for showing statistical significance. Merely showing there is an effect does not demonstrate that effect is of the same magnitude as expected.

Conversely, experiments 5 and 6 have a very large number of controls, relative to the experimental conditions. This is wasteful, certainly, but it could also throw off the analysis: since the confidence interval narrows as more samples are taken, we can tighten one side up by throwing more datapoints in and taking advantage of the p-value’s weakness.

Experiment 6 might show this in action. For the first fifty subjects, the control group was further from the null value than the negative image group, but not as extreme as the erotic image one. Three months later, the next fourty-one subjects are further from the null value than both the experimental groups, but this time in the opposite direction! Here, Bem drops the size of the experimental groups and increases the size of the control group; for the next nineteen subjects, the control group is again more extreme than the negative image group and again less extreme than the erotic group, plus the polarity has flipped again. For the last fourty subjects, Bem increased the sizes of all groups by 25%, but the control is again more extreme and the polarity has flipped yet once more. Nonetheless, adding all four runs together allows all that flopping to cancel out, and Bem to honestly write “On the neutral control trials, participants scored at chance level: 49.3%, t(149) = -0.66, p = .51, two-tailed.” This looks a lot like tweaking parameters on-the-fly to get a desired outcome.

It also shows there’s substantial noise in Bem’s instruments. What’s the odds that the negative image group success rate would show less variance than the control group, despite having anywhere from a third to a sixth of the sample size? How can their success rate show less variance than the erotic image group, despite having the same sample size? These scenarios aren’t impossible, but with them coming at a time when Bem was focused on precognition via negative images it’s all quite suspicious.

The Control Isn’t a Control

All too often, researchers using frequentist statistics get blinded by the way p-values ignore the null hypothesis, and don’t bother checking their control groups. Bem’s fairly good about this, but we can do better.

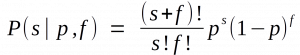

All of Bem’s experiments, save 3 and 4, rely on Bernoulli processes; every person has some probability of guessing the next binary choice correctly, due possibly to inherent precognitive ability, and that probability does not change with time. It follows that the distribution of successful guesses follows the binomial distribution, which can be written:

where s is the number of successes, f the number of failures, and p the odds of success; that means P ( s | p,f ) translates to “the probability of having s successes, given the odds of success are p and there were f failures.” Naturally, p must be between 0 and 1.

where s is the number of successes, f the number of failures, and p the odds of success; that means P ( s | p,f ) translates to “the probability of having s successes, given the odds of success are p and there were f failures.” Naturally, p must be between 0 and 1.

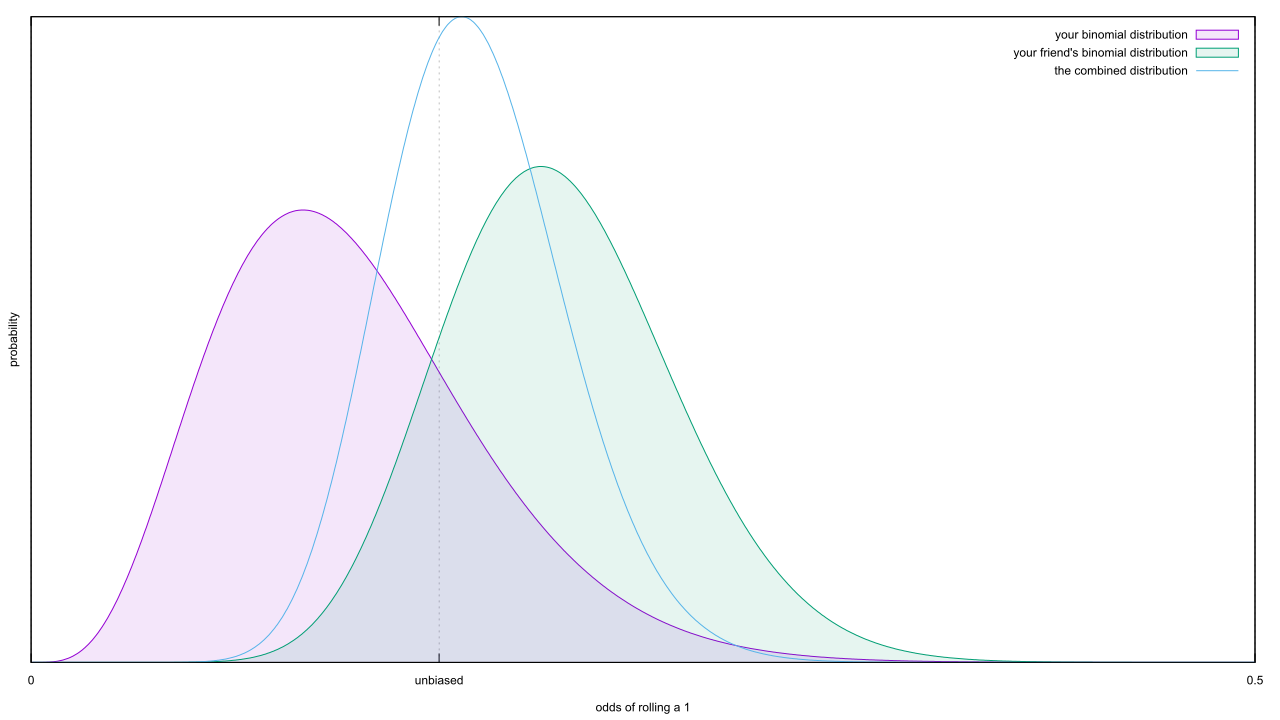

Let’s try a thought experiment: say you want to test if a single six-sided die is biased to come up 1. You roll it thirty-six times, and observe four instances where it comes up 1. Your friend tosses it seventy-two times, and spots fifteen instances of 1. You’d really like to pool your results together and get a better idea of how fair the die is; how would you do this? If you answered “just add all the successes together, as well as the failures,” you nailed it! The results look pretty good; both you and your friend would have suspected the die was biased based on your individual rolls, but the combined distribution looks like what you’d expect from a fair die.

The results look pretty good; both you and your friend would have suspected the die was biased based on your individual rolls, but the combined distribution looks like what you’d expect from a fair die.

But my Bayes 208 post was on conjugate distributions, which defang a lot of the mathematical complexity that comes from Bayesian methods by allowing you to merge statistical distributions. Sit back and think about what just happened: both you and your friend examined the same Bernoulli process, resulting in two experiments and two different binomial distributions. When we combined both experiments, we got back another binomial distribution. The only way this differs from Bayesian conjugate distributions is the labeling; had I declared your binomial to be the prior, and your friend’s to be the likelihood, it’d be obvious the combination was the posterior distribution for the odds of rolling a 1.

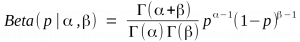

Well, almost the only difference. Most sources don’t list the binomial distribution as the conjugate for this situation, but instead the Beta distribution:

But I think you can work out the two are almost identical, without any help from me. The only real advantage of the Beta distribution is that it allows non-integer successes and failures, thanks to the Gamma function, which in turn permits a nice selection of priors.

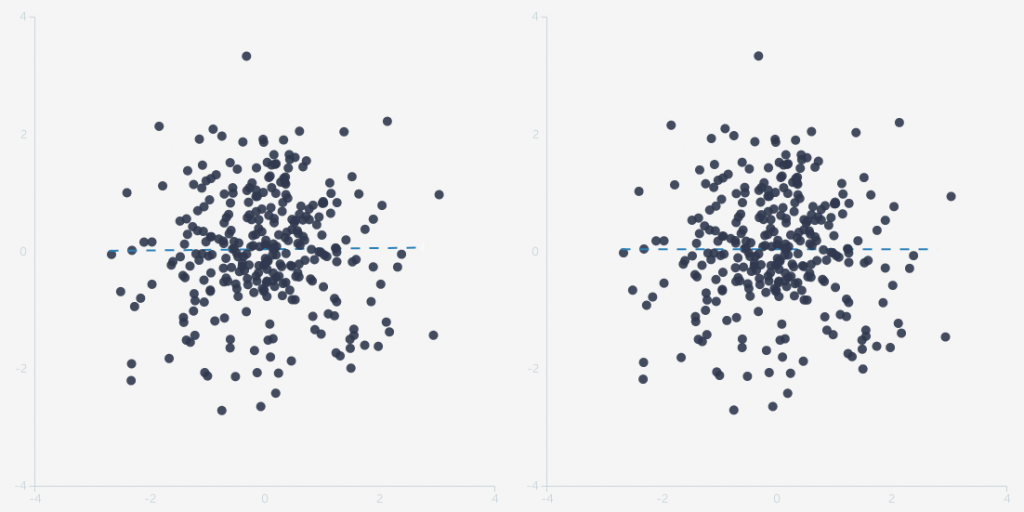

In theory, then, it’s dirt easy to do a Bayesian analysis of Bem’s handiwork: tally up the successes and failures from each individual experiment, add them together, and plunk them into a binomial distribution. In practice, there are three hurdles. The easy one is the choice of prior; fortunately, Bem’s datasets are large enough that they swamp any reasonable prior, so I’ll just use the Bayes-Laplace one and be done with it. A bigger one is that we’ve got at least three distinct Bernoulli processes in play: pressing a button to classify an image (experiments 3, 4), remembering a word from a list (8, 9), and guessing the next image out of a binary pair (everything else). If you’re trying to describe precognition and think it varies depending on the input image, then the negative image trials have to be separated from the erotic image ones. Still, this amounts to little more than being careful with the datasets and thinking hard about how a universal precognition would be expressed via those separate processes.

The toughest of the bunch: Bem didn’t record the number of successes and failures, save experiments 8 and 9. Instead, he either saved log timings (experiments 3 and 4) or the success rate, as a percentage of all trials. This is common within frequentist statistics, which is obsessed with maximal likelihoods, but it destroys information we could use to build a posterior distribution. Still, this omission isn’t fatal. We know the number of successes and failures are integer values. If we correctly guess their sum and multiply it by the rate, the result will be an integer; if we pick an incorrect sum, it’ll be a fraction. A complication arrives if there are common factors between the number of successes and the total trials, but there should some results which lack those factors. By comparing results to one another, we should be able to work out both what the underlying total was, as well as when that total changes, and in the process we learn the number of successes and can work backwards to the number of failures.

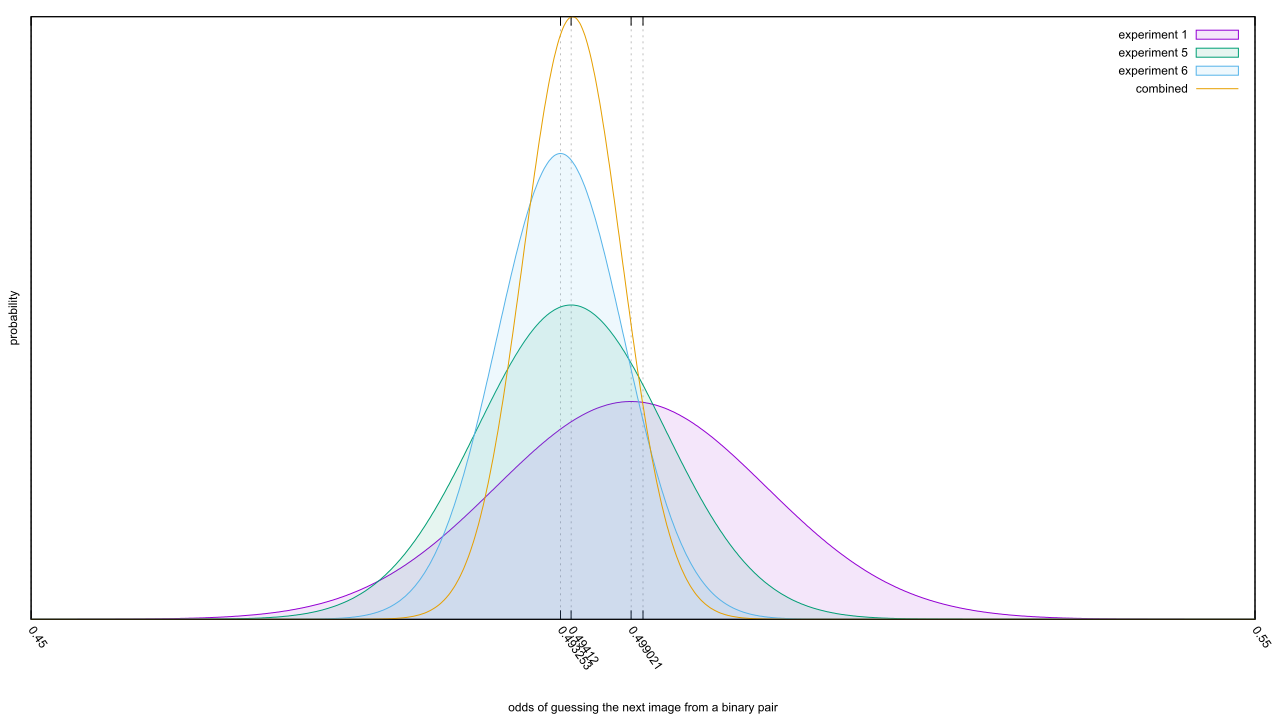

As the heading suggests, there’s something interesting hidden in the control groups. I’ll start with the binary image pair controls, which behave a lot like a coin flip; as the samples pile up, we’d expect the control distribution to migrate to the 50% line. When we do all the gathering, we find…

… that’s not good. Experiment 1 had a great control group, but the controls from experiment 5 and 6 are oddly skewed. Since they had a lot more samples, they wind up dominating the posterior distribution and we find ourselves with fully 92.5% of the distribution below the expected value of p = 0.5. This sets up a bad precedent, because we now know that Bem’s methodology can create a skew of 0.67% away from 50%; for comparison, the combined signal from all studies was a skew of 0.83%. Are there bigger skews in the methodology of experiments 2, 3, 4, or 7? We’ve got no idea, because Bem never ran control groups.

… that’s not good. Experiment 1 had a great control group, but the controls from experiment 5 and 6 are oddly skewed. Since they had a lot more samples, they wind up dominating the posterior distribution and we find ourselves with fully 92.5% of the distribution below the expected value of p = 0.5. This sets up a bad precedent, because we now know that Bem’s methodology can create a skew of 0.67% away from 50%; for comparison, the combined signal from all studies was a skew of 0.83%. Are there bigger skews in the methodology of experiments 2, 3, 4, or 7? We’ve got no idea, because Bem never ran control groups.

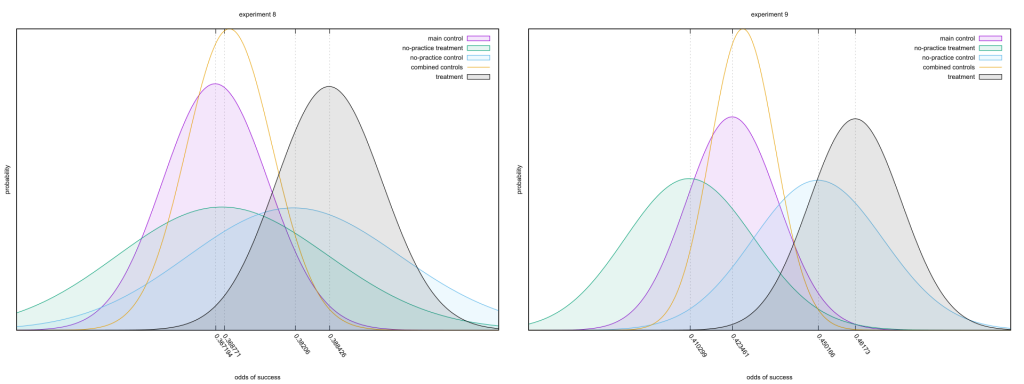

Experiments 3 and 4 lack any sort of control, so we’re left to consider the strongest pair of experiments in Bem’s paper, 8 and 9. Bem used a Differential Recall score instead of the raw guess count, as it makes the null effect have an expected value of zero. This Bayesian analysis can cope with a non-zero null, so I’ll just use a conventional success/failure count.

On the surface, everything’s on the up-and-up. The controls have more datapoints between them than the treatment group, but there’s good and consistent separation between them and the treatment. Look very careful at the numbers on the bottom, though; the effects are in quite different places. That’s strange, given the second study only differs from the first via some extra practice (page 14); I can see that improving up the main control and treatment groups, but why does it also drag along the no-practice groups? Either there aren’t enough samples here to get rid of random noise, which seems unlikely, or the methodology changed enough to spoil the replication.

Come to think of it, one of those controls isn’t exactly a control. I’ll let Bem explain the difference.

Participants were first shown a set of words and given a free recall test of those words. They were then given a set of practice exercises on a randomly selected subset of those words. The psi hypothesis was that the practice exercises would retroactively facilitate the recall of those words, and, hence, participants would recall more of the to-be-practiced words than the unpracticed words. […]

Although no control group was needed to test the psi hypothesis in this experiment, we ran 25 control sessions in which the computer again randomly selected a 24-word practice set but did not actually administer the practice exercises. These control sessions were interspersed among the experimental sessions, and the experimenter was uninformed as to condition. [page 13]

So the “no-practice treatment,” as I dubbed it in the charts, is actually a test of precognition! It happens to be a lousy one, as without a round of post-hoc practice to prepare subjects their performance should be poor. Nonetheless, we’d expect it to be as good or better than the matching controls. So why, instead, was it consistently worse? And not just a little worse, either; for experiment 9, it was as worse from its control as the main control was from its treatment group.

What it all Means

I know, I seems to be a touch obsessed with one social science paper. The reason has less to do with the paper than the context around it: you can make a good argument that the current reproducibility crisis is thanks to Bem. Take the words of E.J. Wagenmakers et al.

Instead of revising our beliefs regarding psi, Bem’s research should instead cause us to revise our beliefs on methodology: The field of psychology currently uses methodological and statistical strategies that are too weak, too malleable, and offer far too many opportunities for researchers to befuddle themselves and their peers. […]

We realize that the above flaws are not unique to the experiments reported by Bem (2011). Indeed, many studies in experimental psychology suffer from the same mistakes. However, this state of affairs does not exonerate the Bem experiments. Instead, these experiments highlight the relative ease with which an inventive researcher can produce significant results even when the null hypothesis is true. This evidently poses a significant problem for the field and impedes progress on phenomena that are replicable and important.

Wagenmakers, Eric–Jan, et al. “Why psychologists must change the way they analyze their data: the case of psi: comment on Bem (2011).” (2011): 426.

When it was pointed out Bayesian methods wiped away his results, Bem started doing Bayesian analysis. When others pointed out a meta-analysis could do the same, Bem did that too. You want open data? Bem was a hipster on that front, sharing his data around to interested researchers and now the public. He’s been pushing for replication, too, and in recent years has begun pre-registering studies to stem the garden of forking paths. Bem appears to be following the rules of science, to the letter.

I also know from bitter experience that any sufficiently large research project will run into data quality issues. But, now that I’ve looked at Bem’s raw data, I’m feeling hoodwinked. I expected a few isolated issues, but nothing on this scale. If Bem’s 2011 paper really is a type specimen for what’s wrong with the scientific method, as practiced, then it implies that most scientists are garbage at designing experiments and collecting data.

I’m not sure I can accept that.