Dang, I need to correct something I wrote.

Every human right applies to every person, equally. When rights conflict, one is temporarily granted precedent. It’s why the Canadian Charter of Rights and Freedoms is ordered the way it is; rights listed earlier in the document are more important than those listed after, greatly simplifying the analysis of any rights conflict.

I’d gotten that impression because Section 1, which allows any right to have restrictions placed on it to preserve a safe and free democracy, was placed up front while later sections deal with things like elections and criminal trials. In reality, they’re all “indivisible.”

Human rights are indivisible. Whether they relate to civil, cultural, economic, political or social issues, human rights are inherent to the dignity of every human person. Consequently, all human rights have equal status, and cannot be positioned in a hierarchical order. Denial of one right invariably impedes enjoyment of other rights. Thus, the right of everyone to an adequate standard of living cannot be compromised at the expense of other rights, such as the right to health or the right to education.

=====

All human rights are indivisible, whether they are civil and political rights, such as the right to life, equality before the law and freedom of expression; economic, social and cultural rights, such as the rights to work, social security and education , or collective rights, such as the rights to development and self-determination, are indivisible, interrelated and interdependent. The improvement of one right facilitates advancement of the others. Likewise, the deprivation of one right adversely affects the others.

=====

All human rights are universal, indivisible and interdependent and interrelated. The international community must treat human rights globally in a fair and equal manner, on the same footing, and with the same emphasis.

This, of course, makes dealing with conflicting rights much more complicated. Usually, you have to demonstrate significant harm to place limits on a right; for instance, in Canada we allow restrictions on free speech only because they can cause physical harm and a loss of security, while even prisoners and foreign nationals are granted “full access to Canada’s human rights protections.”

Note also that these restrictions come from the state, not private individuals. Google cannot throw you in prison or seize your home, and even when they vacuum up your private info that’s only because they claim you agreed to give up a few specific types of personal information when dealing with them or authorized third parties, and because they can point you to tools that allow you to delete any data they have on you. Liability waiver forms shield some of the parties to the contract from being sued in connection to what happens in a specific time and place, they don’t prevent you from launching all lawsuits and they don’t prevent lawsuits in the case of extreme gross negligence. In no case can a private individual or corporation unilaterally take away a right, and any action that could place limitations on a right must be done by mutual consent.

I think you know where I’m going with this, especially since EssenceOfThought got there first, but humour me. The UN Declaration of Human Rights wasn’t considered legally binding on all countries that signed it at the time, but it’s evolved into precisely that while also expanding to encompass new rights.

Victor Madrigal-Borloz, the Independent Expert on protection against violence and discrimination based on sexual orientation and gender identity, said Advisory Opinion OC-24 issued by the Court on 9 January 2018 was a significant step toward upholding the dignity and human rights of persons with diverse sexual orientation and gender identity.

Pathologizing persons with diverse gender identities, including trans women and men, is one of the root causes behind the grave human rights violations against them. Madrigal-Borloz underlined that the Court concluded that requiring medical or psychological certifications or other unreasonable requirements for gender recognition was not in line with the American Convention.

“I am very pleased with the Court’s reasoning, which is permeated in equal measure by legal rigour and human understanding. Advisory Opinion OC-24 is a veritable blueprint for States to fulfil their obligation to provide quick, transparent and accessible legal gender recognition without abusive conditions, respectful of free/informed choice and bodily autonomy, as was also exhorted last May by a group of United Nations and international human rights experts,” he said.

Gender identity is a fundamental right, at the highest level. But because it took the UN a while to get there, other countries have already granted that right themselves. At the federal level, Canada made it official in 2017.

For all purposes of this Act, the prohibited grounds of discrimination are race, national or ethnic origin, colour, religion, age, sex, sexual orientation, gender identity or expression, marital status, family status, disability and conviction for an offence for which a pardon has been granted or in respect of which a record suspension has been ordered.

I’m proud to say we even allow non-binary sex designations on our passports. Even my home province of Alberta, one of the most conservative in the nation, considered gender identity a fundamental human right as of 2015.

WHEREAS it is recognized in Alberta as a fundamental principle and as a matter of public policy that all persons are equal in: dignity, rights and responsibilities without regard to race, religious beliefs, colour, gender, gender identity, gender expression, physical disability, mental disability, age, ancestry, place of origin, marital status, source of income, family status or sexual orientation.

If gender identity is a human right, then private organizations cannot prevent individuals from being treated according to how they identify, unless both parties mutually consent. If one person says “no,” then any such differential treatment is a human rights violation. Only the state can say otherwise, and even then only if the alternative does significant harm.

So when Rationality Rules says this …

[19:00] And my answer to the more controversial question, “do trans women who have experienced male puberty have an unfair athletic advantage?” is: it depends on the sport. […]

… he’s arguing that private organizations should have the ability to suspend human rights, and that rights are divisible, contrary to decades of legal precedent across multiple countries. And when he says this …

[20:02] I am not opposed to trans women who have experienced male puberty competing in the female category of SOME events because they’re trans. I am opposed because the attributes which are granted from male puberty that play a vital role in some events have not been shown to be sufficiently mitigated by HRT. It’s not about whether or not they’re women, it’s about whether or not “fair play” has been maintained. Do I make myself clear?

… he is making himself abundantly clear. He considers the maintenance of “fair play” in sports vital to the operation of a free and fair democracy, so vital that it justifies removing human rights from some transgender people. In the process, they’ll have fewer rights than convicted criminals.

There’s two ways to rescue Rationality Rules from this absurdity. One is simply that he’s ignorant; in the two months he spent researching the topic and consulting with biologists, physiologists, and/or statisticians [17:50-17:59], he never ran across the human rights argument. The other way is that he doesn’t agree with the concept of human rights. The second path is kind of awkward, as it has him rubbing shoulders with the religious figures he likes to critique. At any rate, he’s closed off both means of escape.

This video can be considered the remake, and I’ve done my utmost best to illustrate that this is not about people’s rights, it’s about *what constitutes fairness in sport*. You, me and everyone else have the right to compete in sports, but that doesn’t mean that we have the right to compete in any division we want.

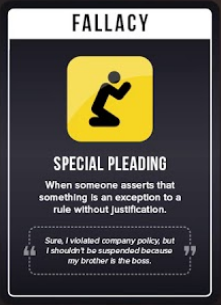

So there’s no dodging it, Rationality Rules is engaging in special pleading. He wants an exception to an existing rule without justification, even if he has to throw out over fifty years of human rights law in the process.

Now, to be fair, everyone makes mistakes. Rationality Rules isn’t the first atheist/skeptic to be guilty of special pleading, and he won’t be the last. In most cases, this just due to ignorance: they don’t know their logical fallacies, and thus don’t realize they’re engaging in them. If he wants to brush up, I’d recommend he play “Debunked.”

Debunked is a highly strategic card game of logic, reason and nonsense! There are two decks, one full of fallacious arguments, and the other full of everything else – which includes logic to debunk the arguments, ways to improve your hand (such as resurrecting a card from the discard pile), and, most importantly, ways to mess with your opponent (such as making them skip their go). It’s very simple to learn, but hard to master… like logic itself. …

I know it’ll help him in this particular case, because it contains a “special pleading” card.

The card game is currently a Kickstarter project, so the only way he can get a copy is to contact…. oh. Oh dear.

… Hey, I’m Stephen Woodford, the man behind the YouTube channel Rationality Rules, and this game is my attempt to combine my two loves – reason and gaming. Debunked is first and foremost a thoroughly enjoyable and repeatable game, saturated with varying strategies and hilarious themes, but it’s also a fantastic tool for learning logic; the arguments are real, and so too are the fallacies they commit – hence, the logic cards genuinely can teach people a thing or two about valid argumentation (or at the very least remind them).

If you thought I was exaggerating when I said “he’s lost his grip on reality,” bear in mind that I had this card up my sleeve at the time. It had plenty of company, too.

[HJH 2019-07-14: Finally got around to adding the “fair play” link.]