I hate visiting the same place in the mountains twice, yet I’ve been to Lake O’Hara…. shoot, nine times? I’ve lost count. That should tell you something about the place.

It’s become a problem for me, actually. O’Hara has an obscene number of trails, but even a weak hiker can see the best of the best in four days. I’m scrambling to find new things to see there, sometimes quite literally: Yukness Mountain’s true peak is too intense for me, but scrambling up the false North peak is not. Mount Schaffer was off-limits, until I learned of the easy route from Lake McArthur, and there’s a “Little Odaray” I could work myself up to. On the less vertical side of things, Duchesnay Pass and Mount Stephen’s SE peak have been high on my to-explore list, but they’re both 30km days.

That leaves Abbot Pass Hut. Oh sure, the scramble to it is a grind, and there isn’t much to do there unless you’re a climber. The hut is a character in itself, however. Named after the first mountaineer to die in North America and situated next to “The Death Trap,” an unstable glacier with a well-earned name, it balances between death and life in a way that’s rare for a tourist site. This tends to inspire people.

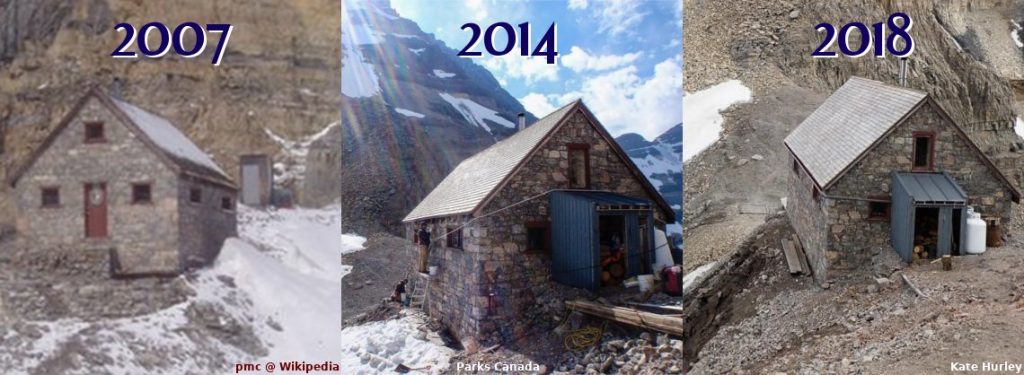

The Abbot Pass Hut still occupies my dreams and my nightmares. It is a fearsome structure that lords itself over a terrible moonscape. Set impossibly high in the Rockies, its construction in 1923 requiring extraordinary human guts and determination, the hut is a rare work of heroic architecture. There’s nothing embellished or frivolous about the cabin, nothing pretty. The thick stone walls of the hut are as unforgiving and sublime as the cliffs that surround it on all sides.

Seen up close, the hut is the essence of the classic picturesque, a central wooden door with flanking windows under a pitched roof, enough room for about 25 people to prepare meals in a kitchen, dine on pasta around a pot-bellied stove and sleep in the loft upstairs. It was designated a National Historic Site in 1992, and there’s nothing complicated about its form. On a skinny col between Mounts Lefroy and Victoria, where storms can dump a metre of snow in the middle of August, the architecture has been devised to ask only a bare minimum from the site — enough fieldstone to create its walls, enough room to set itself down. One metre is all you get between one side of the hut and a sheer drop of cascading rock.

It used to be at the top of my to-do list, and I even had plans to visit it earlier this summer, but that “one metre” has shrunk.

The Death Trap has retreated, weakening some of the rocks beside the hut. Parks Canada has shut the hut down, and even banned people from approaching while engineers assess the situation. My dream of visiting the hut may never come true, and it’s all thanks to climate change.

If you are an avid hiker, the thumbprint of climate change is everywhere. Scenic viewpoints where you could get a great view of the mountains are no longer scenic; as the climate warms and carbon dioxide increases, the treeline shifts upwards and trees get taller. Animal habitats change, for instance Alberta winters are no longer cold enough to kill off the Mountain Pine Beetle and they’ve taken full advantage. Warmer weather brings bigger storms and more frequent droughts, feeding forest fires that ruin high-elevation views and could potentially kill off half of Alberta’s forests.

And, most obvious of all, the glaciers are retreating.

That sign says “In 1911, the Alpine Club of Canada marked the toe of Robson Glacier at this point. The glacier recedes approx. 15m (52ft) a year”. See that small smear of white underneath the dark mountains in the background? That’s the toe of Robson Glacier, one century after that marker.

It’s obvious that climate change exists, once you know where to look, and it is equally obvious we’re losing ground even as we expose more of it.