Mano Singham and PZ Myers aren’t that interested in eclipses. I’m sort of the opposite, as a group of us drove 13 hours to reach totality, arriving only an hour and a half before the eclipse started… and departing for the return trip fifteen minutes after totality ended. Why the heck would anyone go to such extreme lengths for a few minutes of darkness?

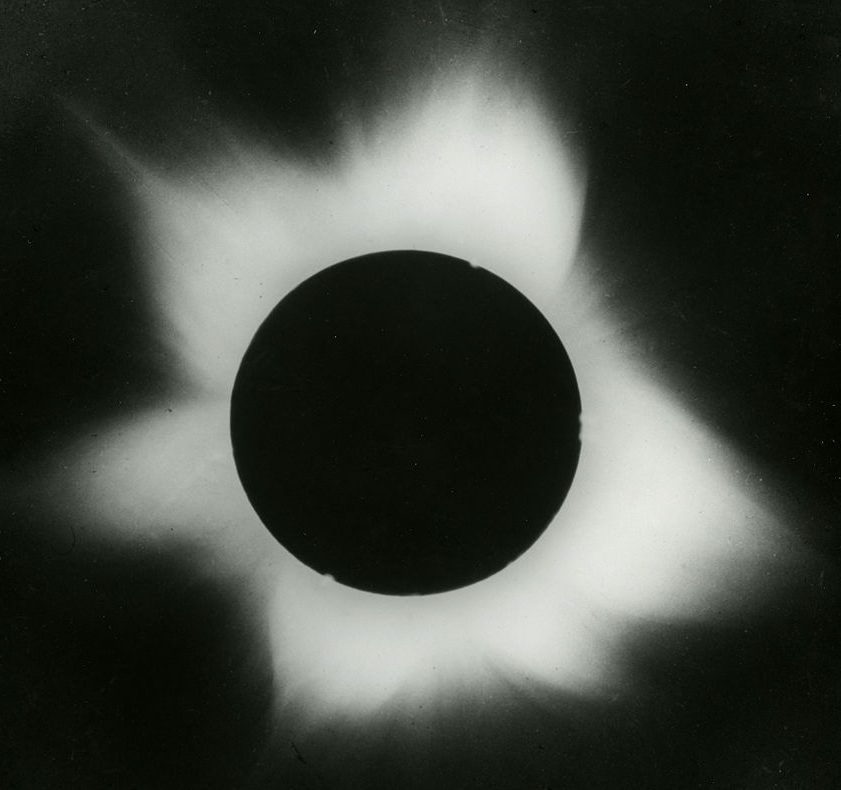

The Corona

The solar corona is the hottest part of the sun we can see, far hotter than the surface, and we don’t know why that is. Despite being so hot, the corona is also very diffuse and thus the cooler chromosphere blasts out far more light than it does. This means you can’t see it if any part of the sun is visible, and the physics of choronographs means they block off significantly more of the corona than the Moon does during an eclipse.

While that’s all very nice and intellectual, there’s also something satisfying about looking up in the sky and seeing what looks like Albert Einstein being consumed by a black hole.

Mercury

Mercury

The planet Mercury is likely the last visible-eye planet discovered. Because it clings so tightly to it, you need to blot out the Sun by exploiting sunsets and sunrises, and even then you need a view close to the horizon and the planet in a certain orientation. A solar eclipse accomplishes the same, only during the middle of the day. I’m not convinced I actually saw Mercury yesterday, as it was faint and appeared in the wrong spot too close to the sun, but oh well.

Sunsets on Every Horizon

I can verify this actually happens. The physics is pretty simple: the Moon’s shadow occupies a finite area. If you’re perfectly centred under it, every horizon is in the direction of a patch of earth which has at least some sunlight falling on it. That sunlight bounces back up into or scatters through the atmosphere, producing something that looks like a sunset. It is wicked cool!

Watching The Shadow

The shadow of the Moon is quite fuzzy, so if you’re expecting to see a sharp line you’ll be disappointed. The best view is definitely from space, though an airplane will do in a pinch; on Earth, I could spot the Eastern horizon getting gradually lighter even as we were in totality.

Shadow Bands

As NASA puts it, “Shadow bands are thin wavy lines of alternating light and dark that can be seen moving and undulating in parallel on plain-coloured surfaces immediately before and after a total solar eclipse.” Scientists aren’t entirely sure what they are, but the best guess is atmospheric cells warping light in a similar way to stellar flicker. They aren’t guaranteed to show up, but I insisted on laying out a white blanket to make them more visible. We missed seeing them as totality was approaching, but as the Sun started peeking back I strongly suggested everyone stare at the blanket. And we saw them!

A Chill In The Air

The Sun radiates a lot of heat our way, which is absorbed and scattered by the ground and atmosphere. Take away that source, and you’re just left with the radiation from said ground and atmosphere as it cools down. This is at its strongest during totality, and collectively we could feel the atmosphere was notably chillier just after the eclipse than it was in the lead up. I’m estimating the difference was about 5-10C.

People Losing Their Shit

My photos of the eclipse were pretty lousy, as I didn’t have any money to invest in the proper gear. Derek Muller of Vertasium was much luckier, but his video is more notable for the audio; he, and everyone around him, were losing their minds as they reached totality. You don’t get that from a partial solar eclipse.

Don’t listen to Singham or Myers. Total solar eclipses are the coolest, and if one happens to fall near you I recommend you take full advantage.