Earlier this semester, I gave my first-year students a thought question. I do this now and then just to wake them up and get them thinking and talking — in this case, I wanted them to speculate and also think hard about how they came up with their answers, and how they would try to evaluate them. Here’s the question:

Anatomically modern humans first appear in the fossil record about 150,000 years ago. The first record of systematic agriculture appears about 10-15,000 years ago. The Industrial Revolution began about 300 years ago. People nowadays seem to be coming up with new ideas at an increasingly rapid pace. What’s going on? Why did it take ancient hunter-gatherers over 100,000 years to invent farming, but going from the invention of the airplane to passenger jetliners took less than a century?

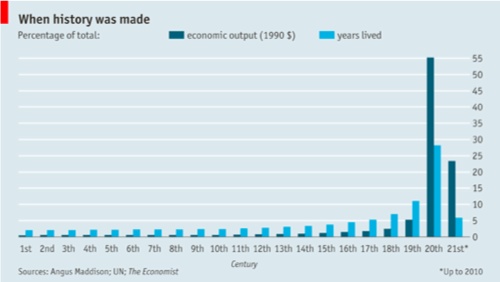

Now The Economist comes up with an interesting chart that might explain some of that.

SOME people recite history from above, recording the grand deeds of great men. Others tell history from below, arguing that one person’s life is just as much a part of mankind’s story as another’s. If people do make history, as this democratic view suggests, then two people make twice as much history as one. Since there are almost 7 billion people alive today, it follows that they are making seven times as much history as the 1 billion alive in 1811. The chart below shows a population-weighted history of the past two millennia. By this reckoning, over 28% of all the history made since the birth of Christ was made in the 20th century. Measured in years lived, the present century, which is only ten years old, is already “longer” than the whole of the 17th century. This century has made an even bigger contribution to economic history. Over 23% of all the goods and services made since 1AD were produced from 2001 to 2010, according to an updated version of Angus Maddison’s figures.

The figure is a little murky: the units and axes aren’t clearly explained. The bars are percentage of the total, so “years lived” actually means the percentage of the total number of human years lived. So when “years lived” for the 20th century reads out as about 27, that means that 27% of all the years lived by all humans occurred in the 20th century.

I might show this graph to the class next year when I ask the question, but I’d still get to emphasize that the how of knowledge is really important: a serious flaw in the chart is that they don’t explain how they came up with, for instance, their estimate of relative economic output in the 5th century.

The 21st century is off to a roaring start, isn’t it?

(Also on Sb)

“By this reckoning, over 28% of all the history made since the birth of Christ was made in the 20th century.”

Their use of the birth of christ leads me to ignore the whole piece as probably flawed.

And much of that knowledge has resulted in environmental and human degradation.

I’ve always assumed that the apparent increase in speed of innovation correlated with the increase in the ability of humans to share knowledge with each other (printing press, postal services, telegraph, telephone, internet …). Whether there’s also causation there, I don’t know — but I’d like to think so. We all build on the work of others, but it’s hard to do so unless you’re aware of the work of others.

Prompting Mr. Ray Kurzweil to the stage?

I have no idea what this even means. How do you graph history? What are they quantifying? The amount of printed words? Printed plus images carved on rocks? What? I don’t get it.

Correct me if I’m wrong but isn’t the answer, Moore’s Law? Esssentially the fact that future endeavours are built on the successes of present ones. Which were in turn strengthened by the minor abilities of our past? You know, the whole standing on the shoulders of giants and all that jazz.

Agree with comment #1. Why did they toss in that arbitrary date, and why did they refer to a mythological person (“Christ”) instead of an (allegedly) historical person (“Jesus”)? If The Economist wants to be seen as a serious publication, I sure hope they use BCE and ACE instead of BC and AD.

There was a huge change when Newton finished up a coherent view of physics, and how we can actually figure things out in meaningful ways. The fuse was long (compared with our current pace of change, that is), but it led to a whole lot more happening, including much larger populations.

Until we finally had a coherent view of reality there wasn’t much clear about how to get from an observation to a meaningful change in results for ourselves. There were bits and pieces of “science,” but in many ways things still seemed sort of magical, such as getting metals from their ores (you go through the steps, yet no one knows why, exactly, the steps result in what you want).

Once we had a framework of understanding, knowledge built up enormously, although each piece of knowledge seems on average to be less and less useful to us.

Biological information became useful to us much later than did physics information, although biology generally is much less tractable than are machines. Physics had its fights with religion in the 16th century primarily, biology mostly in the 20th and early 21st centuries–and until, when?

Glen Davidson

Yeahbut, it has also resulted in a huge increase in life expectancy.

(dons engineers hard hat)

I put it down to engineering, mainly Civil Engineering (huge improvements in water supply, sewage treatment and food storage (much of which took place ahead of the science))This allowed more and more people to have time to think and do things not immediately connected to survival. Life for those fortunate enough to be born in the more developed world were able to live lives that were no longer ‘Nasty, brutish and short’.

Yeah, yeah. Kipling wrote better ‘Just So’ stories.

I’ll expect the cheque by return.

(hard hat off)

(crossposted from Sb)

Funny thing is, this works just as well with the “grand deeds of great men” view of history. If there are 7 times as many people now as in 1811, that means there are (on average) 7 times as many “great men” alive now than in 1811, and again 7 times as much history is being made.

In any case, it’s interesting that the 20th and the 21st centuries are unique in having a greater share of money than of people. I suppose a Marxist view of history, where all history is the history of economy, fits this chart just as well as a “grand deeds of great men” view!

It is interesting to me that we can see that some insect colonies work as a single organism, but few are ready to accept that is true of humans as well. Part of this reluctance is our incredibly strong feeling of individuality. It seems clear to me that humans work as colonial entities, and as communication has improved as a single, if somewhat disorganized one.

In small simple societies, inventive progress was limited because everyone had to spend much of the day in dealing with food. As societies got bigger, it did not take everyone to bring in the crops so specialization started and we got things like language.

Technological and scientific progress evolves from what has gone before. The more tricks you learn, the bigger your toolbox of tricks and so it easier to develop new ones.

The huge acceleration of such progress today is a function of three things.

1. There being many more brains at work, with a vast amount of specialization

2. decreased barriers to communication both in terms of language and with opening of the internet

3. With the increasing level of knowledge and technology already established we have a much larger array of tools for further advances.

It seems clear to me that technology will advance in a geometric progression.

If this headlong rush into galactic obscurity continues…thangs are going to go sproinnnngggg…ka-blam…tinkle tinkle tinkle… sound of metal dustbin lid spinning itself into its ground state!

This cannot be sustainable methinks…can it?

I can’t get too worked up about the “christ” talk. It is an entirely arbitrary date.

Anubis Bloodsin III:

Of course it’s sustainable. Just not with the resources of earth.

A thought that struck my mind reading this was the old series that James Burke did (“The Day the Universe Changed” in the 80s and “Connections” in the 70s). From the research he did, most inventions are not huge leaps in thought or knowledge, but are largely ideas that build on each other…basically incremental changes to ideas that someone else had thought of earlier, who had built their idea from someone else earlier, etc.

This being the historical case, it really shouldn’t be a surprise that, with many more people around, that the net number of changes just continues to increase.

In my own industry, I can assure you that the computer you are using today connected to the servers that host this site are not drastically different than what existed 3 or 4 decades ago. There have just been a whole lot of incremental changes during that time that has resulted in the internet, user interfaces, and software that we use today.

Sounds too strongly correlated to assume anything causal, but it is interesting to see. It would make sense that population growth is pretty closely tied to new innovations (agriculture was an obvious one), but wouldn’t go so far to assume that the opposite is true.

Just wait until the oil runs out. Then all of that history goes right back down where it belongs. Or we can wait for global warming, or the massive die-off of ocean life coming up. Take your pick, the big bad is coming, and there is no technological fix.

Well, as an economist (a marxist economist, in the same sense that PZ is a darwinist biologist, that is acknowledgeing the genius of those men, but also their ignorance), I think that capitalism is a huge explainer of that. But not only capitlism, science as well. As a matter of fact I think boh are interrelated and feed each other. The way the capitalist economy works, it subordinates all other kinds of economic relationships to the “holy hunger of gold” nad the best way to feed that hunger is to create new commodities or new and better (with less cost and more output) ways of producing them. For that, science and technology are stimulated, research must be done. On the other hand, these technologies must work, so, as the scientific method gets better results, it is “capitalistally selected”(hey, I’ve just invented the phrase capitalist selection, that works in similar ways as artificial selection or natural selection). Capitalism feeds science and vice-versa. But not only because of that, but also because science needs a freedom environment that prior organizations of production, as slavery or feudalism didn’t provide.

The explanations offered by the authors of the graph are silly, because they don’t explain why suddenly the population’s rate of increase rocketed – and it is the rise of science (Hygiene and medicine) and of methods of producing food and health items that explained that.

Well, of course the increase in communication media and the better interaction of larger amounts of people are important, but they only happened in this environment of capitalism and science feeding each other.

I would argue that we don’t have seriously ‘splaining to do after the onset of agriculture a dozen-ish millenia ago. From there, the advance of technology and human knowledge seems to follow a pretty clean curve of exponential increase. And this makes sense since more technology helps us acquire more knowledge (both directly and indirectly), and more knowledge helps us get MOAR TEKNOLOGIE!, and so forth.

What I think does require an explanation is why the 150,000 years of lag time between anatomically modern (and presumably behaviorally modern, though we can’t know for sure) humans and the advent of agriculture? You can’t even chalk it up to a black swan event, because agriculture seems to have arisen independently in several parts of the world at around the same time (give or take a few thousand years, of course).

A few speculations:

* A hundred thousand years is a good long time for natural selection to do some work, and it’s possible our cognitive abilities increased significantly in that time. There are many problems with this idea, but it might have contributed somewhat.

* Agriculture requires a period of co-evolution between humans and plants, and it may be that this just took a long ass time. This also can’t be a complete explanation, though, because domesticated plants appeared in multiple places in the world only a few thousand years apart. Those who have read Guns, Germs, and Steel will have a good feel for the significance of this. I imagine this could explain several millenia of the lag time, but nowhere near a hundred thousand years.

* Critical mass of human population? I think this has the causality the wrong way, i.e. the human population took off because of agriculture, not the other way around.

I don’t know what else…?

Not entirely, because although fairly good collections of writings exist from somewhat before the Roman Empire, it’s often convenient to start with the Roman era due to better knowledge from that time, and because it had been the last great European civilization prior to modern civilizations. “Christ” is somewhat later than the Empire itself, sure, but for our purposes it’s pretty much close enough to the beginning of Pax Romana that it is used for that reason, and also due to how our time is reckoned.

“Christ” is also conventional language for speaking about “from that time.”

Glen Davidson

A lot of quibbling over terminology here. I’d rather discuss the graph than the social merits of the starting point or dating convention that aren’t even listed.

I think there are three main reasons why there is such a correlation between population and innovation. First, what the author implies but does not say, that every person is essentially an opportunity for a good idea and when you increase the number of people and the population density, not only are innovative ideas and practices more likely to be formulated but they are also more likely to spread quickly.

Second, what was stated above by Dragon83uk, that each innovation builds on what came before.

Third, and what I’ll be throwing in, is the whole “necessity is the mother of invention” thing. Canard as it may be in conventional use, the basic idea has merit in this case. The planet has a certain carrying capacity for each species that inhabits it. In pre-agricultural times when humans survived on what they could hunt or gather, that number for humans would have been relatively small, maybe fifty or a hundred million. Also keep in mind the Toba event 70,000 years ago knocked humanity on its ass population-wise right in the middle of its existence (so far). Once population levels reach their maximum carrying capacity, they start bumping against a bell curve that results in starvation, conflict, etc. And while this situation is normal for most species, that’s when people start thinking about ways to get more food for themselves and their, family, tribe and society along with ways to store that food and protect it. Also keep in mind that the carrying capacity is different for different parts of the world, which may be why the agricultural revolution occurred first in North Africa and Asia Minor instead of central Africa, Europe or the Americas. This happens again during the 18th and 19th centuries when humans, again, meet the limits of the current paradigm. Following Europe’s emergence from feudalism, the Americas (newly depopulated by disease and the other effects of “colonization”) served as a kind of population heat-sink: the global population could grow without reaching carrying capacity because vast amounts of hither-to un-tamed land was being converted for agricultural use. This is also not taking into account the many other social factors from about 2000 BC to the end of the middle-ages that kept population sizes relatively stable. So, industrial revolution increases the carrying capacity from about 1-1.5 billion up to about 4 billion. Then in the 20th century the petroleum revolution increased it again. It’s still unclear how GMOs and other new technologies will eventually increase the carrying capacity, but most estimates give the population as peaking in 2050 at about 10 billion due to the inverse relationship between standard of living and reproduction rates. But “peak oil” might start to force equilibrium sooner. Remember that all of these innovations (agriculture, industry, petroleum) are artificial increases in the Earth’s carrying capacity for humans and should something make one of those processes impossible (such as running out of petroleum that isn’t prohibitively energy-intensive to extract) then the population it had allowed would no longer be sustainable and it would result in a population crash. But barring that, should we reach 10 billion, who’s to say that some OTHER technology won’t expand the potential population size again?

@4 – *laughs*, I hope other people get the joke.

I agree with @6 (shoulders of giants) and @3 (idea transmission) but I also think that a lot of it is the attitude of society to new knowledge. Religion and other cultural breaks have been resistant to change but the main cause may be that for a long time most people just didn’t see new thought as interesting. It was only when, post the take off of the ‘science meme’, new inventions started to turn up with a relative high frequency (i.e. during one person’s lifetime) that the average person started paying attention.

I think the y axis should be scaled logarithmically… In the representation above, any changes the early centuries are basically invisible from the scaling effect.

Also, since my post was long and I didn’t see others’ comments until I submitted it, I see a lot of people pointing to things like better communications, different economic systems, science, certain theories and individuals as “reasons” for the increases in population.

It is true that some of these things did facilitate larger populations and better communication between those populations (Gutenberg’s press was an AMAZING catalyst for the process of innovation as a whole). But this is missing the point, I think. These developments are part of a process. Better communication becomes necessary, then it becomes available and facilitates far more than merely satisfying the needs of the inventors. Same thing can be said of most of the examples given and it is also important to remember that when less energy is necessary to satisfy basic necessities, people actually have time to sit down think, invent and administrate.

These are little cogs in a gear: they get you to the next cog, but they’re not the driving force behind the process. This is a matter of the relationship between population and innovation, and while innovations often facilitate greater populations, pointing to specific individual innovations as though they were spontaneous and could have occurred serendipitously at any time in history to change the world misses the bigger picture.

Something is not exactly right in the explanation. Let’s suppose there are twice as many people at time Y than at time X. Well, it doesn’t mean that they’ll make “twice as much history”. They’ll make much more than this, because the level of education and knowledge has increased between X and Y, as has the technical environment, and so has the “history-making power” (the correct word would be productivity) of each person.

If it were possible to make a graph showing the speed of knowledge.

I’m sure we’de see a big boost after the invention of speech, then another huge boost after the invention of writing, printing,schools, computers, internet etc…

It all boils down to education basically.

The easier it becomes to gather and share knowledge, the faster we can improve upon it.

At just 10 years of age, there are kids that know more and are more capable then the most intelligent people a couple of hundred years ago…

And yet, they just keep on cutting education fundings!!!

This is similar to something Robert Anton Wilson remarked on some time ago: The Jumping Jesus Phenomenon

I think the ever-increasing scope of our knowledge and speed of technological development are primarily due to both population size and information management.

By effectively preserving the knowledge we acquire, we’re essentially reaping the rewards of intellectual compound interest; with no need to reinvent the wheel (both literally and figuratively – unless we’ve got some free intellectual capacity to invest such “luxury knowledge”), we can move on to inventing better things to do with the wheel.

As our population increases, so, too do the total number of intellectual outliers; if Einsteins are 1 in a million (a number just I pulled out of America’s cultural ass), then there are currently 6000 Einsteins in the world. Three hundred years ago, there were only 900 Einsteins.

And once we began to effectively disseminate the accumulated knowledge we had (through both increasing species-wide literacy rates – since up until recently, a lot of our knowledge was preserved in books – and increasing access to the the knowledge), we were able to ever-more-effectively capitalize on the increasing number of Einsteins (fewer of whom were relegated to lives of toil that made ineffective use of their intellectual gifts).

And, of course, for every Einstein, there are thousands of other brilliant folks who don’t become quite so famous and who comprise much of the metaphorical body of the giants upon which famous intellectuals stand.

I suspect things will be getting ever-more interesting, until either our knowledge management systems or population base (or both) collapse.

Moore’s Law is, itself, actually a rather nice example of this trend of drastically increasing knowledge and technology; back in the 90’s some thought Moore’s Law would fail, since microprocessor design was running up against the limits of optical wavelength (for etching circuits) and quantum effects (for maintaining wire integrity). A lot of money got a lot of smart people working on it, and Moore’s Law weathered that storm just fine.

On a tangent, my dad likes to tell people how the ancient Greeks, for all their intellectual achievements, know so little that a person could literally become a master of all knowledge (a philosopher), and nowadays, we know so much that a person can’t even master all knowledge in a single field (like biology).

Shut up historical numpties!

I too have grave concerns over how they got their numbers. It’s inconceivable to me that the 6th century – the midst of the European dark-age, before the Islamic explosion, during the collapse of the Gupta Empire and the civil-war filled Southern and Northern Dynasties of China – had as great an economic output as the 1st century when Rome, Parthia, Satavahana and the Han Empire were at their height.

That said, I have a question for Dr. Meyers; What would your reaction be to a student who answered your question by positing something akin to Jaynes’ bicameralism theory of human consciousness?

Be champions!

I remember someone in a history class in college making a statement to the effect of “There are more people alive right now than have ever died”. Our professor paused, considered, and said “You may be right”.

Whether he was right or not in flat numbers, this chart does agree with that statement in a different way.

SO why the fuck am I still having to work ~40 hours a week like a goddamn chump?

@ Brownian

It’s prolly ’cause ya don’t got Jeebus in yer heart….

@ Sarcen #21

It’s always a pleasure to read something that makes me consider an aspect of population growth I hadn’t considered before (what caused us to leave the hunter-gatherer life to one agriculturally-based). That “A-ha!” feeling is very satisfying – thanks for providing it!

I wonder though how a perfectly-acting, reversible form of birth control would affect these issues. We’re smart enough to see the benefits of producing our own food instead of fighting over the resources, could we be smart enough to limit our growth instead of producing new resources now that we have the technology to do so? I doubt it, but it’s fun to think about. Assuming it was universally used, would it stagnate innovation? How would we have to adjust our economies? How would we avoid classic science fiction scenarios of birth quotas and dome-life??

Megan: For the record, it’s actually not true. The math that leads to that analysis assumes a n^2 increase in population where n = the number of generations that have ever lived. However, as any population graph would indicate, the population has remained relatively stable for most of history, with big jumps over short spans of time (agrarian revolution, industrial revolution, etc.).

According to this around 105 billion people have been born in the last 10 thousand years, vs the 7 billion alive today.

Reading this thread makes me want to play more Innovation.

Homo sapiens evolve at 195ka not 150ka.

My guess would be that the rate of progress in science and technology is a function of the total amount of man hours spent on research and development multiplied by the ability of people to “stand on the shoulders of giants” multiplied by the amount and quality of infrastructure and machinery.

I would guess a combination of population size and depletion of the amount (numbers and sizes) of big game and selecting for game with effective running away from humans behavior.

If the Crude Awakening documentary is be believed, OIL is responsible for much of economic output of the last century. It`s made for cheap transportation, food growth and exponential growth of the human population. The documentary asks how well we will do once all the easy oil is used up? (Also, if wealth growth is reliant on exponential growth of the human population, and that is unsustainable, what happens then?)

Lots of great comments on the actual topic. I liked what Sailor said:

The huge acceleration of such progress today is a function of three things.

1. There being many more brains at work, with a vast amount of specialization

2. decreased barriers to communication both in terms of language and with opening of the internet

3. With the increasing level of knowledge and technology already established we have a much larger array of tools for further advances.

We’re smart enough to see the benefits of producing our own food instead of fighting over the resources, could we be smart enough to limit our growth instead of producing new resources now that we have the technology to do so?

You’re suggesting that agriculture reduced conflict between groups? Agriculture upon adoption served the needs of local elites much more than the other 99% of people, who likely would have been better off remaining horticulturalists and semi-nomadic pastoralists depending on environmental factors. (Agriculture creates surplus long term, but year by year it makes starvation among the sedentary and densely housed peasantry a near certainty sooner or later. Also for most it’s a life of backbreaking toil where hunter-gatherers take it relatively easy. Not to mention the diseases.) One of the first innovations following agriculture is warfare –not that hunter-gatherers and pastoralists didn’t ever fight over resources, but typically the first thing elites wanted to do with their new surpluses of grain and population was feed an army.

Agriculture also produces surplus people. You need a few extra hands come planting and harvest time, but when those hands grow up and need their own farms, the family farm can only be subdivided so much.

Lastborn sons and daughters were born to plunder.

Critical mass of human population? I think this has the causality the wrong way, i.e. the human population took off because of agriculture, not the other way around.

All that was required was a local critical mass of population. In Mesopotamia, as more and more horticulturalists settled in the river valleys taking advantage of the rich alluvial deposits, villages grew into unmanageably large agglomerated settlements and somewhere along the line the devil’s bargain was struck: more security, less autonomy for almost the entire population. Following that, and outside the most densely populated areas, “conversion” to agrarian living was often acheived by force as the new cities annexed as much land as they could.

Oh, this thread is threatening to drive me back into my “I wish I were !Kung” melancholy.

I’ll just stare at my grey cubicle walls and pasty, flabby belly, and think how incredibly lucky I am that I’ll have forty more years of this bone-numbing tedium before I can retire and spend my days trying to remember the passwords that make all of this wonderful, life-enhancing technology usable. I hope the Palin/Bachmanns of the future don’t nuke us all before I get a chance to kill a morning with Angry Birds 2050.

Silvia @ #18 —

I’m still under construction as a scientist (finishing up my undergrad work, applying to grad programs, doing a part-time research internship), but I’ve seen situations where the relationship between science and capitalism is much less productive. In cases where research on science which may later lead to technology-based applications is being done by either private companies or universities which are shifting to a capitalist “business” model…the capitalist concerns can stifle, rather than encourage, scientific research. If scientists at different institutions can share research-in-progress (or, better, collaborate on research), this helps the process along; but if institutions treat the physics, chemistry, biology, etc. as trade secrets, scientists working on the same problem have to duplicate the groundwork without reference to each other (instead of collaboratively developing a model and then independently testing it). At this point, a capitalist mindset (including on the part of socialist institutions like public universities) becomes a drag on science rather than a stimulus.

(I mean, really…does the capitalist model of psychology effectively describe scientists — or anyone other than would-be CEOs and robber barons, for that matter? I mean, sure, most of the scientists in my family and circle of friends like having money — but as motives for their research go, profit is rather lower on the list than curiosity, the thrill of discovery, and basking in the adoration of one’s peers and the public when the research goes really well. Offer a scientist a choice between lots of money and perpetual obscurity on the one hand, a moderate income and everlasting glory on the other…well, you get the idea.)

Various factors have been mentioned for the change over the last 2000 years (the Economist’s time period), many good, although how much each is consequence and how much further cause would be important in any in-depth analysis. I mentioned Newton, more as a sort of culmination than as a lone event (in reality it was a continuation, yet it continued with quite a difference).

But of course if Newton is a sort of culmination, what caused physics to move forward at that time? Well, the Renaissance and reason were already ascendant, of course, but why that?

Looked at in one way, the biggest single reason for the increase in knowledge, economy, and population is probably the printing press. Nothing new in the world, and even the success of the printing press in Europe was due in large part to increasing curiosity, study, and knowledge already occurring in the Renaissance. The latter probably had roots in the Crusades, at least in that it was such a widespread and enduring movement at the time (mini-Renaissances had happened previously, but didn’t keep their energies for too long).

The printing press, however, facilitated the Renaissance and was part of what led to physics, Newton, and the Enlightenment (Newton had something to do with thought toward rational government, it should be noted, although he himself was likely monarchist to the hilt). It was the first information revolution facilitating communication and preserving knowledge for future generations in to a degree far greater than had occurred in the past. Writing was good, cheap printing in large volumes was rather better.

OK, not a staggering revelation. It’s just that not too much of what did occur after Gutenberg would have done so to the same degree as if we hadn’t had the printing press. Looked at in another way, though, it is possible that the printing press was more the result of paper reaching the West (a reasonably-priced writing and printing medium at last), and to the Renaissance needing it, than that the printing press itself was any great breakthrough. Using blocks for fancy writing, seals, and other precursors of printing had existed for thousands of years, and presumably it could have been invented much earlier, even though better knowledge of metals did facilitate Gutenberg’s invention. There really wasn’t much of a market for it before the Renaissance, especially since parchment or vellum would make even printing expensive (Gutenberg did print some parchment or vellum Bibles, however I think few printed on those afterward).

So I have doubts that printing was more cause than result of what was already happening. Necessary it was for the rate of knowledge growth which followed, but once there was a cheap printable medium and enough demand, the printing press probably was more or less inevitable. Indeed, maybe it was “invented” because of reports of printing from the East, yet I don’t really doubt that it could have been invented in the West without those. It’s a fairly obvious development once you have stamps and seals, which had long been in existence, and just has to become economical to do.

Glen Davidson

What, 32 comments, many long & analytical, yet nobody has mentioned the word “Singularity” yet?

Anyway, never mind — P.Z., what were your students’ replies like? Please do a post recapping their responses. Or have them blog their answers on their class blogs.

Kurzweil was mentioned at #4, however.

Glen Davidson

Let me offer you a sketch of the argument.

0. It has little to do with population.

1. First, it is the invention/perfection of ways of acquiring knowledge. This includes scientific method, concentration of knowledge (libraries) and domain experts (universities).

2. Second, the organization of society conductive to furthering of new ideas. This includes improved industrial capacity (can implement new ideas) and improved financial systems (can raise money and resources to try new things out).

the “invention” of farming was a major turning point that is clear for all the reasons that have been stated already.

What exactly is meant by farming? is it the “domestication” of certain food plants? OK those plants did not reproduce or spread so well by themselves. That does not mean that humans did not encourage some food plants over none food plants without having formal farms or farm fields more in the way of horticulture than farming.

Many none farming peoples practice brush burning as a way to encourage fresh growth for animals that they hunt while that is not farming it is certainly modifying the natural environment for their own benefit.

looks to me that one of the things that is similar with at least all the seeds (grains) we grow is they all have them all tightly bound together and must be separated compared to wild grasses whose seeds readily spread apart. That all over the world at about the same time we discovered grasses that shared that is interesting. The only thing I can say is we were obviously looking at these seed baring plants pretty closely for some time. Many hunter/gatherers have seed beaters and gather wild seeds. It seems likely that some seeds would be planted wild sometimes be gathered later when they were ripe.

so I don’t think that farming came all of a sudden but was significant was the discovering of grass that really needed more help to grow than the “traditional” grass seeds they/we had been eating until then.

on population growth I seem to have read in various places that as people become more prosperous the birth rate goes down. Like most things about humans it seems to be very much influenced by cultural things and not just the same biology imperatives of the rest of biology.

interesting ideas about the effects of population numbers on development.

I do have a question though. What is history and what is meant by more history. Is history what we did in the past? Or is there some other criteria imposed on the “raw events” of what we did in the past. Is there a cultural bias to what is called history and what is called the past and what is worth remembering as history?

Is the story of my family and all the people that make it up not history?

If history is the story of lives of people the more people you have the more stories you will have.

so what does any of it mean or does it mean anything?

uncle frogy

Surely it’s just a whole host of virtuous cycles, such as:

Better technology for survival/sustenance -> less time per individual spent on survival/sustenance -> more time to develop technology for survival/sustenance -> back to the start

Better technology for commmunicating ideas -> ideas are spread around to more people -> old ideas used as a basis for more ideas by more people -> back to the start

Better medicine allows people to live longer -> longer lives means more time can be spent thinking and observing -> more thinking and observing leads to new ideas about medicine -> back to the start

Add that to the expanding population courtesy of our better ideas, and the ever-growing giants on whose cumulatively massive shoulders we stand, and an exponential increase is all we can really expect. Go human race.

Human population growth has not been exponential. In exponential growth, the proportional increase remains the same every year.

Until the 1960s human population growth was superexponential – the proportional increase itself was increasing and had been probably throughout the Christian era, possibly with a couple of bumps for major epidemics. Since the 1960s it has been subexponential – after peaking at about 2.4% per annum, the proportional increase has fallen to about half that. Since sometime in the 1990s, even the absolute yearly increase has declined slightly. So, maybe super-exponential growth in population is essential to capitalism, and the decline is behind the current crisis?

For agriculture to work, you need a reliable climate. You simply don’t get that in an ice age.

You also don’t get it in Australia. There were a few tribes who occasionally sowed the seeds of edible plants before a rain and then harvested afterwards, but none of them ever made itself dependent on this, because in Australia you have no guarantee on when, or even whether, it will rain next year.

It’s failing now, though. That’s why there are dual-core and quadcore computers now.

Well, no. Pretty much only agriculture and Pacific Northwest salmon-fishing allow people to accumulate to such densities that elites can even form. Otherwise, tribes stay at a size of around 150 people and don’t turn into stratified societies.

Of course, at least in the Fertile Crescent or rather just north of it, people only started to eat grass seeds when they had run out of antelopes and then of acorns. Agriculture comes from starvation.

I’m not at all sure I’d choose fame over financial security with money left to donate. I’m not in it for fame, I’m in it for fun – the joy of thinking, of surprise, of discovery. Not everyone is an extrovert like your straw-scientist.

Indeed, scientists are forced to seek fame by pretty draconian measures: the job market is small, and fame is almost a prerequisite for getting hired.

Agriculture comes from starvation.

David, you need to make the distinction between horticulture and agriculture. Hunter-gatherer economies cannot be transformed into agrarian economies in the absence of already existing ones due to scarcity as you’re saying. There are intermediate steps. So in Mesopotamia a long period of horticulture of greater and lesser intensity and pastoralism must have obtained for cereal cultivars and the forebears of sheep and goats and cattle even to be selected, yes?

Starvation can happen in a season. The adoption of agrarian economies and the accretion of the first cities must have taken centuries, at least.

#39 CJO –

You’re suggesting that agriculture reduced conflict between groups?

No, but I could certainly see how human populations at that time could think it might. I doubt they could anticipate what would come to pass when the idea first came to mind of, “We can’t find enough food to feed our tribe, and we can’t fight that other tribe who gathers in that area over there, but what if we use these seeds from this tasty plant, and make sure they all grow?”

That’s a misunderstanding.

Moore was essentially talking about components per dollar in his famous 1965 article. He predicted that the number of transistors per dollar would grow nearly perfectly exponentially between 1965 and 1975. The trend has had it’s ups and downs over the years, but the average growth has been roughly the same and it still holds to this day according to those who count.

The current trend in consumer electronics is that it’s already good enough and therefore most of the gains are passed on to the consumer in the form of lower cost rather than more transistors.

This means that you’re somewhere to the left of the minimum on the graph in the first figure in Moore’s article (except it’s the graph for 2011 and the transistor counts are about a million times higher). So in some sense Moore’s law for consumer electronics is failing because the consumers do not want faster computers.

Server farms still go for the sweetspot in that graph. They’re buying 8-core and 12-core processors at present.

@43 M Groesbeck

You misunderstood me. I don’t think scientists have a profit oriented way of living or thinking. At least, not necessarily. But they must live and must have laboratories and must have independence. And capitalist institutions, including the capitalist State are more adequate to finance that than feudal ones.

Catholics like to say that their institutions were very important to science. I doubt that. They wouldn’t give the monks enough freedom to really go further. When you read about science in the XVIth and XVIIth centuries, a lot of the big names had to flee from various types of organized religion. More freedom was necessary to the upsurge of science, as well as more money (and by money I mean literally money, in the sense of a type of wealth that is “general” and “interchangeable”, what Marx called abstract wealth, as opposed to the concrete wealth a subsistence economy creates. It is only when everybody is working for money and not directly for bread and other daily needs, that it is plausible to accumulate huge amounts of resources needed for science and take them away from the production of the goods that can provide for those daily needs.

david cortesi:

Neither has anyone mentioned the Eschaton, either.

(Your point?)

I always though that looking at history in a population weighted time scale would be interesting (i.e increments of 1 tic per 500M people year lived). My interest was more about technology progress than economics but i does kind of look like the economic out put on a population weighted scale would level out substantially.

So I went to the link(thanks, Sarcen) and it all made sense until I came to this:

WTF_YIKES! How actually fast can a basic feature, such as the rate of growth to maturation (and also to living long enough to ensure the survival of your children) change in a population/species?!? ie, from 5 to about 15 yrs. of age?

Coincidentally, they lived in dog years time frames to us now, therefore 1 of their years = 7 of ours. This means that they of child bearing age after 2 chronological years(14yrs of our lifespan), were old enough to drink when 3 yr. old. Men were in their sexual prime at ~2.5 – 3 yrs., women 6 – 7.

Serious now, more likely they would develop child rearing maturity at around seven years old, and seeing infant mortality was between 50 and 80%, they had to sire 4 or 6 kids, and care for them long enough that they could survive on their own, so more likely they were physically developed enough to start producing babies at 5 yrs. of age!

No wonder it took them so long to invent farming, they were still playing with barbie dolls and playing cops and robbers when they died of old age!

Fuck farming, it’s time for my milk and cookies!

One more item of note, PZ asks his students this:

I respectfully submit that your comparison to the paradigm shift of scrounging to farming would be more analogous to first cars -> walking on the Moon in ~100 yrs. or to put another way, 1/1000th the time for farming to appear. (Gunpowder to atom bomb? Leeches to heart transplants? Comic books to movies of comic books? For instance?)

Start of the Singularity? Looks more like the start of a bell curve to me.

@ #58 tushcloots:

You seem to misunderstand what is meant by average life expectancy. This was actually explained to me many years ago by my high school history teacher when a student seemed confused that all of our founding fathers were in their 70s and 80s at a time when the average life expectancy was around 35. It is an easy mistake to make because the media regularly uses it in the wrong terms, so let me try to clear this up.

Average life expectancy is not an indicator of expected age at time of natural death from old age, but is rather and average age of death for all individuals in the population. In the neolithic age, it is reasonable to consider that they probably had an infant mortality rate of around 75%, that is to say that only one in four people made it past the age of 5 due to disease, malnutrition or one of the many other hazards. Add to this that most of the people who made it past 5 didn’t get past their 20s due the fact that back then minor injuries usually meant certain death (a compound fracture of the finger meant sepsis, gangrene and death, a cut on the bottom of the foot meant sepsis, gangrene and death, childbirth that didn’t go 100% perfectly meant either sepsis or internal bleeding and death, and so on).

Also, the younger a person is when they die (say, 1-5 years old), the more they skew the statistics for potentially long-lived species. This also explains why the average life expectancy in parts of Africa and the Pacific rim are in the 30s and why that number varies from country to country based mostly on whether there is an ongoing civil war or famine/drought.

So the reason that the average age then was low is because of the extremely high rate of unnatural death and very early ages, not because of potential life-span. If you took someone from that era into today, they would probably not live past about 40 due to epigenetic regulation, but their children would probably have the same lifespan as you or me.

I hope this make more sense to you now.

Sarcen, thanks. Yeah, here I am yakking about 50-80% infant mortality, and then forgetting exactly what you have explained clearly, here.

If 8 die in first year, 2 surviving for 50 years = ~ 100yrs/10 births.

I was going to make a joke about Moses et al living for 900 yrs. and how many babies the dinosaurs must have eaten to bring the avg. life expectancy @birth down to ten years, even!

It seems to me that there are 2 primary reasons for the escalating rate of discovery: population density and the speed at which information can travel among the population.

As the population density increases more and more time is freed for innovation and free thought. A hunter-gatherer society would have less time available for purely mental activities than say a farming village. As the population density icreases the stratification and specialization of society increases untill we reach the point today where you have some people that only make food, some people who only fix broken items, and people who only design new things, etc.

Today only a small percentage of the population is required to provide the food and shelter required by all freeing vast segments to create new ideas and new uses of existing ideas.

The speed at which information travels also is a strong factor. The increasing level of human knowledge has steadily increased as our ability to spread ideas has increased.

The first major advance in the speed of idea transmission (outside of mass migrations) was the invention of writing. For the first time an idea could be presented without the physical verbal transmission of the idea. Next came animal domestication (horses and oxen) which allowed faster travel and faster spread of ideas. The pace of innovation truly began picking up steam with the near simultaneous advent of the first electronic communication methods (telegraph, radio, and telephone)and the steam engine.

It was my understanding that power dissipation was the limiting factor in processor clock speeds today, rather than transistor count.

The Natufians (the people you’re talking about there) were sedentary before they started growing crops – the acorns were enough to form a basis for a sedentary population; and sedentary probably always means stratified, although not necessarily to the extent of a chiefdom. I’m not sure about the other places cultivation started, but it seems unlikely it could get far until people were fairly sedentary – you have to protect your crops. There are halfway houses between h-g and agricultural societies today in the Amazon and New Guinea – people grow crops and keep animals but also gather and hunt. It’s very unlikely literal starvation was the spur – in a famine, with no outside aid, a lot of people, particularly children, will die, and thus relieve population pressure for generations. Much more likely is a gradual shift in which those who “intensify” more just slightly outbreed those who do so less, and enough children are produced in total to keep the population growing.

Yes, the greatest decade of innovation in ICT was perhaps the ’60s – the 1860s, that is. During that decade the first transatlantic cable (and the first from Europe to India) were laid. The time to send a message from London to New York fell from more than a week to a few minutes – no single thing since has cut transmission times by a greater margin. I have a book on the history of the telegraph called The Victorian Internet. Ah, if only Charles Babbage had had an organisational genius to match his technical prowess! The late 19th century would have had a cogwheel-and-steam-powered worldwide web!

Steam punk has already been invented.

‘Tis,

I know.

I tried to replot the data on what I call a Population Weighted Year (PWYr).

A PWYr is unit based on a fixed number of years lived in a population. A plot on a PWYr scale, redistributes the years over some reference period, so that they are proportional to the number of years lived in PWYrs.

Hi there, simply turned into alert to your weblog thru Google, and found that it is really informative. I am gonna be careful for brussels. I will be grateful in the event you continue this in future. Lots of people will probably be benefited from your writing. Cheers!