72 years ago, the US advanced the state of the art in war atrocities by detonating a 20 kiloton nuclear weapon in the air over the city of Hiroshima.

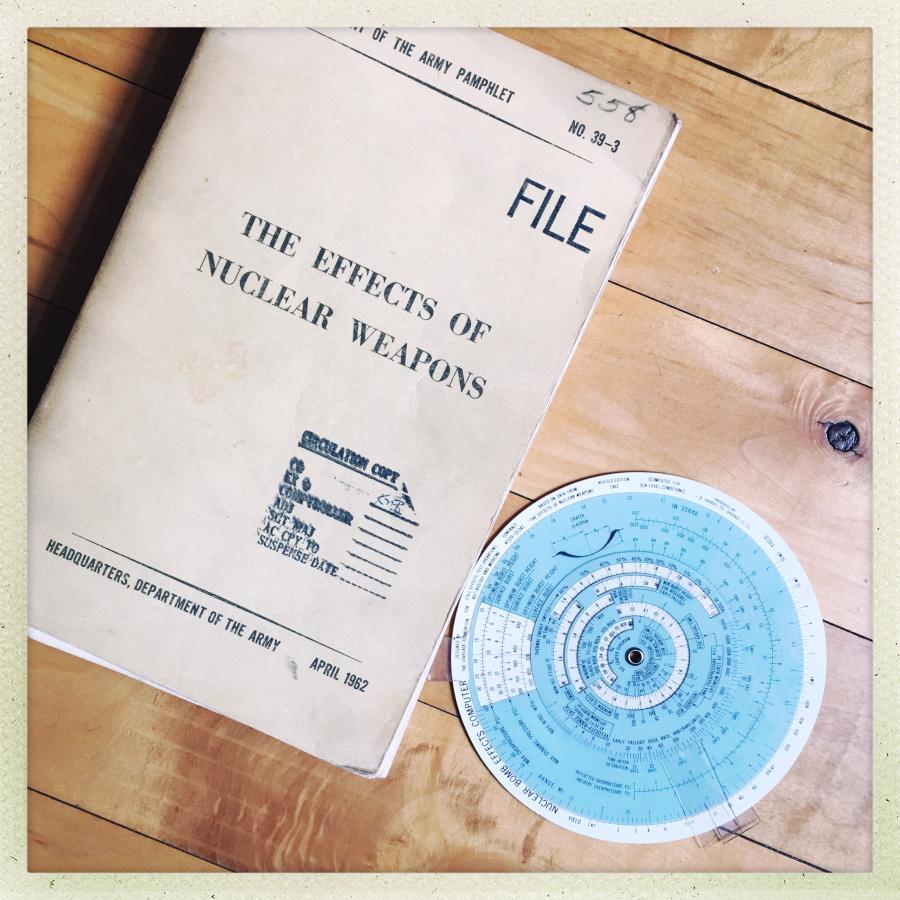

(from my library)

There are many accounts from survivors, who instantly were shifted from “having a fairly ordinary day” to “dying of third degree burns or worse” if they were within 1/2 mile of the epicenter. Three things horrify any thinking person when it comes to nuclear weapons: 1) the suddenness, 2) the indiscriminate destruction, 3) the effects on the survivors. In milliseconds, and for milliseconds, your body is exposed to temperatures that would melt lead, like a strobe-flash going off – and then you’ve gone from healthy to wounded or dying. In an air attack like at Dresden, at least you could try to run or hide and survive. I think there’s some cognitive bias in effect; the same one that makes people feel they have a better chance of winning the lottery if they get to pick the number: nuclear weapons are a lottery where someone else picks the numbers, instantly, and they’re almost all zero.

Today is a day we can pause and reflect that political leaders around the world have this in store for us. If one or another of them fails in their threat-display games, they will solemnly convince themselves – as they did before they killed 70,000 in a flash at Hiroshima (many more died over weeks, months, and years later) – that it’s necessary. Of course, they have great deeply-buried bunkers and escorts that will get them safely underground so that it’s only the rest of us that have to pay the consequences for their mistakes. It’s necessary!

Hiroshima was perhaps a factor in getting Stalin to rein in The Red Army at the end of WWII – he might not have stopped, and it may have been necessary to threat-display Stalin with the immolation of a few cities of Japanese. But we now know for a fact that the Japanese Empire had been making surrender overtures in May prior to the August use of the nuclear weapons. Alan Dulles even reported to the gathering at the Potsdam Conference (so: Stalin, Churchill, and Truman all knew) in July that the Japanese were asking to surrender as long as they could keep the Emperor in power as a transitional head of state and there would not be war crimes trials like there were in Germany. [amazon] At Potsdam, Truman did not mention the secret weapon at the meeting, but presumably Stalin began preparing for a land-grab in Manchuria and Korea around that time [stderr]. Churchill actually knew more about the US’ atomic weapons program than Truman did; he had been quite close to Roosevelt through the war years. In fact, Churchill concocted “Operation Unthinkable” in June of 1945, which was a set of plans for a surprise attack against Soviet forces in Germany. [wikipedia] At the time the plan was considered fanciful, because the planners didn’t know about nuclear weapons – but Churchill did.

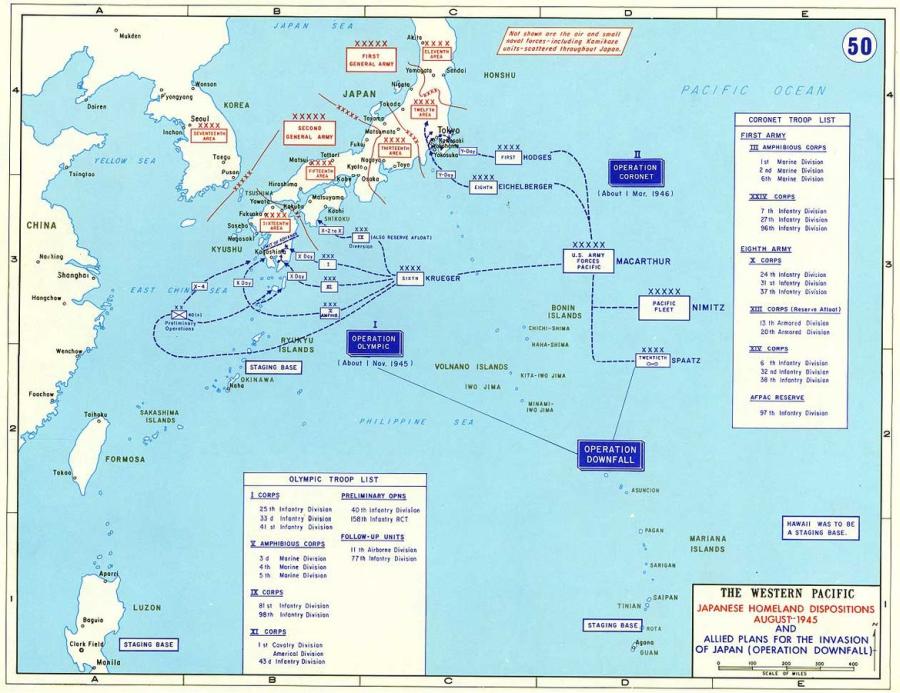

Apologists for the use of nuclear weapons also say things to the effect that the Japanese had decentralized manufacturing and cottage industries in their cities, and there were no other viable military targets. That’s also wrong: the Japanese were expecting an air/sea assault like D-Day or Iwo Jima, and were preparing for it – and so was everyone else. The US battle plan for invading Japan (“Operation Downfall”) [wikipedia] called for a landing in Kyushu, in the south, to draw down the Japanese forces that were digging into the Kanto plain below Tokyo, followed by a second landing in the Kanto, to cut them off and destroy them. Had the Americans been interested in using their nuclear weapons on a military target, there were large military bases in Kanto and Kyushu, where the Japanese were preparing to defend. The truth is that the allies, after the strategic bombing campaign in Europe, had produced a set of commanders who were simply interested in bombing the enemy into oblivion.  Curtis Le May was the most notable; he led the bombing of Germany, Italy, Japan, and eventually Korea in the 1950s. By the time he was bombing Italy, Le May had abandoned any pretense of military targeting or even strategic usefulness: he was out to destroy. It tells you everything you need to know about the US’ leadership that they put Le May in charge of the bombing war over Korea and then put him in charge of the Strategic Air Command – the bombers full of nuclear weapons that Le May tried to talk John Kennedy into releasing during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Curtis Le May was the most notable; he led the bombing of Germany, Italy, Japan, and eventually Korea in the 1950s. By the time he was bombing Italy, Le May had abandoned any pretense of military targeting or even strategic usefulness: he was out to destroy. It tells you everything you need to know about the US’ leadership that they put Le May in charge of the bombing war over Korea and then put him in charge of the Strategic Air Command – the bombers full of nuclear weapons that Le May tried to talk John Kennedy into releasing during the Cuban Missile Crisis.

Operation Downfall, the planned US invasion of Japan

The propaganda around the use of nuclear weapons on Japan is particularly galling, to me, because there are a lot of well-meaning people who – for obvious reasons – believed it. Because they trusted that their leaders shared their interests and values, mostly.

“‘Ey, Grandarse, ‘ear w’at they’re sayin’ on’t wireless? The Yanks ‘ave dropped a bomb the size of a pencil on Tokyo an’ it’s blown the whole fookin’ place tae bits!”

“Oh, aye. W’at were they aimin’ at? ‘Ong Kong?”

“Ah’m tellin’ ye! Joost one lal bomb, an they reckon ‘alf Japan’s in gookin’ flames. That’s W’at they’re sayin’!”

“Wee’s sayin’?”

“Ivverybody, man! Ah’m tellin’ ye, it’s on’t wireless! ‘Ey they reckon Jap’ll pack in. It’ll be th’ end o’ the war!”

“Girraway! Do them yeller-skinned boogers oot theer knaw that?”

“Aw bloody ‘ell! ‘Oo can they, ye daft booger! They ‘even’t got the fookin’ wireless ‘ev they?”

[…]

It was a fine sunny morning when the news, in its garbled form, ran round the battalion, and if it changed the world, it didn’t change Nine Section. They sat on the floor of the basha, backs to the wall, sipping chah and being skeptical. “Secret weapon” was an expression bandied about with cynical humor all through the war; Foshie’s socks and Grandarse’s flatulence, those were secret weapons, and super-bombs were the stuff of fantasy. I didn’t believe it, that first day, although from the talk at Company H.Q. it was fairly clear that something big had happened, or was about to happen. And even when it was confirmed, and unheard of expressions like “atomic bomb” and “Hiroshima” (Then pronounced “Hirosheema”) were bandied about, it all seemed very distant and unlikely. Three days after the first rumor, on the very day that the second bomb fell on Nagasaki, one of the battalion’s companies was duffying with a Jap force on the Sittang bank and killing 21 of them – that was the war, not what was happening hundreds of miles away. As Grandarse so sagely observed: “They want tae drop their fookin’ atoms on the Pegu Yomas, then we’ll git the bleedin’ war ower.” Even then, Nick wasn’t prepared to bet we wouldn’t be going into Malaya with mules; we would all, he prophesied, get killed.

[…]

The war ended in mid-August and even before Nine Section had decided that the fight, if not necessarily done, had reached a stage where celebration was permissible. I joined them in the makeshift canteen, quantities of beer were shifted, Forster sang “Cumberland Way” and “The Horn of the Hunter” in an excruciating nasal croak with his eyes closed, Wedge wept and was sick, Wattie passed out, Morton became bellicose because, he alleged, Forster had pinched his pint, Parker and Stanley separated them, and harmony of a sort was restored with a thunderous rendering of “John Peel” , all verses, from Denton Holme to Scratchmere Scar with Peel’s view-halloo awakening the dead – Cumbrians may be among the world’s worst vocalists but they alone can sing that rousing anthem of pursuit as it should be sung, with a wild primitive violence that makes the Horse Wessel sound like a lullaby, Grandarse red-faced and roaring and Nick pounding the time and somehow managing to sing with his pipe in his teeth.

Like everyone else, we were glad it was over, brought to a sudden, devastating stop by those two bombs that fell on Japan. We had no slightest thought of what it would mean for our future, or even what it meant at the time; we did not know what the immediate effect of those bombs had been on their targets and we didn’t much care. We were of a generation to whom Coventry and the London Blitz and Clydebank and Liverpool and Plymouth were more than just names; our country had been hammered mercilessly from the sky, and so had Germany; we had seen the pictures of Belsen and the frozen horror of the Russian front; part of our higher education had been devoted to techniques of killing and destruction; we were not going to lose sleep because the Japanese homeland had taken its turn. If anything, at the time, remembering the kind of war it had been, and the kind of people we, personally, had been up against, we probably felt that justice had been done. But it was of small importance when weighed against the glorious fact that the war was over at last.

There was certainly no moralising, no feeling at all of the guilt which some thinkers nowaday seem to want to attach to the bombing of Hiroshima and Nagasaki. And because so many myths have carefully been fostered about it, and so much emotion generated, all on one side, with no real thought for how those most affected by it on the allied side, I would like just to look at it, briefly, from our minority point of view. And not only ours, but perhaps yours, too.

Some years ago I heard a man denounce the nuclear bombing of Japan as an obscenity; it was monstrous, barbarous, and no civilized people could even have contemplated it; we should all be thoroughly ashamed of it.

I couldn’t argue with him, or deny the obscenity, monstrosity, and barbarism,. I could only ask him questions such as:

“Where were you when the war ended?”

“In Glasgow”

“Will you answer a hypothetical question: if it were possible, would you give your life now, to restore one of the lives of Hiroshima?”

He wriggled a good deal, said it wasn’t relevant, or logical, or whatever, but in the end, to do him justice, he admitted that he wouldn’t.

So I asked him: “By what right, then, do you say that allied lives should have been sacrificed to save the victims of Hiroshima? Because what you’re saying is that, while you’re not willing to give your life, Allied soldiers should have given theirs. Mine for one, possibly.”

[… much discussion ensues …]

“Well!” he said, looking aggrieved. “Where do you stand?”

“None of your goddam business,” I said, sweetly reasonable as always, “but wherever it is, or was, it’s somewhere you have never been, among people you wouldn’t understand.”

[…]

You see, I have a feeling that if – and I know it’s an impossible if – but if, on that sunny August morning, Nine Section had known all that we now know about Hiroshima and Nagasaki, and could have been shown the effect of that bombing, and if some voice from on high had said: “There – that can end the war for you, if you want. But it doesn’t have to happen; the alternative is that this war, as you’ve known it, goes on to a normal victorious conclusion, which may take some time, and if the past is anything to go by, some of you won’t reach the end of the road. Anyway, Malaya’s down that way … it’s up to you.” I think I know what would have happened. They would have cried, “Aw, fook that!” with one voice, and they would have sat about, snarling, and lapsed into silence, and then someone would have said heavily, “Aye, weel,” and got to his feet, and been asked, “W’eer th’ ‘ell you gan, then?” and given no reply, and at last the rest would have got up, too, gathering their gear and moaning and foul language and ill-tempered harking back to the long dirty bloody miles from the Imphal boxes to the Sittang Bend and the iniquity of having to do it again, slinging their rifles and bickering about who was to go on point, and “Ah’s aboot ‘ed it, me!” and “You, ye bugger, ye’re knackered afower ye start, you!” and “We’ll a’ git killed!”, and then they would have been moving south. Because that is the kind of men they were. And that is why I have written this book.

That, of course, is George Mac Donald Fraser, from Quartered Safe Out Here.

I left some bits out of Fraser’s story, because I didn’t want to type in the entire piece, which is large. Fraser goes into more detailed arguments, but they’re mostly just word-play. I’ve made sure to leave the important parts. By the way, editing a writer like Fraser is a) scary and b) humbling – his thoughts are broken out so cleanly that it’s remarkably easy to find places where you can fast-forward a bit, almost as if he knew that someone would want to do that.

Operation Unthinkable was roundly criticized by military analysts at the time, because it was hopeless: The Red Army would have flattened anything the British, French, and Americans could have fielded at that time. Unless nuclear weapons were involved.

I’ll never forget the look on Sazz’ face when I told him the pretext of the Vietnam War was a lie. [stderr] and I would not want to have had a similar discussion with Fraser. In the full version of his conversation with the philosopher, he touches on more of the standard talking-points around the issue. The important moment, for me, is where he misses the point and has Grandarse say: “They want tae drop their fookin’ atoms on the Pegu Yomas, then we’ll git the bleedin’ war ower.” – they knew, and know, that the bombs were not being used in a militarily useful way. If the US had used atomic weapons on the military forces in the Kanto plain or Kyushu, we would not be having this discussion, I think. And that is what I always have thought. The premise I’ve often heard (even from Fraser) is that hundreds of thousands of allied troops would have died in a seaborne assault. Well, if the beaches had been cleared with nuclear weapons, not so.

I have only ever stolen a few things in my life. In the case of the DA-PAM 39-3, it was in the post library at New Cumberland Army Depot when I visited it, one hot summer around 1986. I stole it. I was probably the only person who ever touched it, so I considered it an act of liberation.

72 years ago.

The propaganda around the use of nuclear weapons on Japan is particularly galling, to me, because there are a lot of well-meaning people who – for obvious reasons – believed it.

At school I was taught that dropping nuclear bombs on Japanese cities was necessary in order to win/end the war. My history textbooks turned USA into the good guys. For a while I believed it, because that was the only interpretation I knew about. It was only some years after finishing school that I accidentally stumbled across some texts written by historians who disagreed with this sugar-coated version.

Maybe another element was ‘military’ curiosity, wanting to see what a nuclear bomb would do to a city in particular. An army base is, by comparison, a rather soft target, I expect. But a city is densely packed with buildings of all sorts, structures that are meant to last, and much more. The people responsible also had been fire-bombing city for some time, so maybe they thought they’d gotten a good ‘feel’ how resilient a city is. Now they simply wanted to see if it could also stand up to one of those new-fangled nuclear things – while there’s till time and excuses to do it. “As we’ve seen, repeated air raids can gradually reduce a city to rubble but it takes time and a lot of resources. Now (maybe) one of the scientists estimates a nuclear bomb could do all that and more in one go? Sounds too good to be true, so let’s try it while we still can.”

—

This article [New Yorker] from 1946 tells the stories of some of the survivors, giving detailed accounts of the attack and its aftermath. It is quite long and occasionally a bit graphic (unsurprisngly) but well worth a read. (I’m not sure where I got it from originally, I don’t think it was from STDERR but if you posted it before, sorry)

chigau@#1:

Fixed; that was a typo. Really!

When I went to Hiroshima and visited the Peace Memorial Museum they showed some of the notes from the meetings where they decided where to drop the bomb. The primary reason for choosing that particular city was because it was relatively untouched by the war. Essentially, they were testing what would happen if you detonated a Nuclear Bomb over a city and Hiroshima had the least confounding variables. It’s pretty chilling when you see how much of the planning around dropping the bomb revolved around scientific measurements rather than military strategy.

My 10th grade english teacher claimed (I have no reason not to believe him) to be part of the force that was supposed to sneak into Japan and commit sabotage in preparation for the invasion, which was considered a suicide mission. So, for him there were two ways the war could have ended, one of which would occur at the cost of his life. While I’m sure he would have agreed that reining in Stalin was a good idea, I’m not sure how important geo-politics are when it’s your neck on the line.

komarov@#3:

This article [New Yorker] from 1946 tells the stories of some of the survivors, giving detailed accounts of the attack and its aftermath.

[I fixed your link above] I believe that’s what eventually became the book “Hiroshima” which I, unfortunately, read at an impressionable age. It got me interested in “where do these things come from?” and drew me away from the more important questions of military strategy until I realized that strategic weapons really aren’t.

Maybe another element was ‘military’ curiosity, wanting to see what a nuclear bomb would do to a city in particular.

drken also bears that point out in #5. I think that, and scaring Stalin, were the two real purposes of the Hiroshima mass murder.

Ieva Skrebele@#2:

For a while I believed it, because that was the only interpretation I knew about.

Me too.

Once you start to realize that governments appear to mostly be made of lies, there’s no way back.

I have the same book in my library, purchased at a used book sale at my alma mater, Arizona State University. It’s a similar edition, published by the AEC but prepared by the DOD. It had been disposed of by the president of ASU at the time, J. Russell Nelson, from his personal library. It includes the Nuclear Bomb Effects Computer. Know where that computer was used in film? Here.

Hi Marcus

I bought my copy of The Effect of Nuclear Weapons by Glasstone and Dolan in the 1970‘s being the latest edition complete with calculator. It is in storage following a house move.

I have seen accusations that it was a propaganda exercise and down played the true damage to support US policy objectives-any thoughts?

My FIL drove Higgins boats in the pacific. He was told to expect 25% casualties during an invasion of the main islands. After Saipan and Okinawa, his personal estimate was 50% killed during the initial assault.

My Dad tried to enlist in January 1942, January 1943, and January 1944, but was refused because he was overage (in his mid-30s) and was employed in a necessary civilian occupation, as a mechanical engineer in a glass-container plant in Terre Haute.

In July of 1945, on his 38th birthday, he was told to report for induction on August 15th.

Just FYI.

fusilier

James 2:24

komarov @3:

I’ve long thought that was the primary reason. About 50 years ago, the thought crossed my mind that they could have demonstrated the power of the bomb without killing anyone (well, hardly anyone). I haven’t heard or read a convincing counterargument to that.

AndrewD@#9:

I have seen accusations that it was a propaganda exercise and down played the true damage to support US policy objectives-any thoughts?

I don’t think so – things like the flash/3rd degree burns radii look to match the caloric output which look to match the yield. It’s certainly possible that the falloff rates are optimistic (or conservative, depending on your perspective) but not propagandistically so.

The main axis of propaganda is the one we’re all familiar with: that the bombing was necessary and justified and saved lives. Only the horrible motherfuckers who run the US would come up with an argument that they put 100,000 civilians in an oven to save lives.

fusilier@#10:

My FIL drove Higgins boats in the pacific. He was told to expect 25% casualties during an invasion of the main islands. After Saipan and Okinawa, his personal estimate was 50% killed during the initial assault.

That’s probably a safe estimate. Except the US could have just accepted Japan’s offer of surrender and there would not have been a landing.

Now here’s a horrifying thought: What if there were no nukes, and rather than accept Japan’s offer of surrender, the US chose to squander 200,000 American and 500,000 Japanese lives in a seaborne assault? Then, afterward, they covered up the offer of surrender in order to justify the necessity of the invasion. That is nearly the scenario we’ve already got, except it was “only” the Japanese that got it in the neck.

Remember: initially, the fact that Japan was trying to sue for peace was concealed from everyone.

siwuloki@#8:

Know where that computer was used in film?

That was where I first saw one!

They’re a nifty piece of work. I’ve always been surprised that they didn’t show up in one of Tufte’s books.

I certainly didn’t expect my grand idea to be particularly novel but I, too, used to simply accept that nuking two cities to end WWII was somehow a necessity. It’s depressing but it took quite some time for me to ask, or wonder, why cities of all things. With Japan already trying to surrender, there is also the question of why nukes of all things.

Part of the reason is, I think, that the war itself is not really covered as part of regular education. History classes received in two (EU) countries covered Nazi Germany right up to the start of the war and essentially stopped there. The same, incidentally goes for WWI, which was mentioned mostly as background for Hitler’s rise and the Russian revolutions. I guess this means the two biggest wars to shape Europe and the world in general don’t offer much in the way of valuable teaching material. They just form the backdrop to the Nazi Thing.*

Now that is an interesting way of putting it, especially with Nazi Germany in mind. The Nazis did the same thing, arguably for the same reason. It’s very apt, apallingly so. I suppose that puts the US leadership in good company, at least for their tastes.

*Which is not to say I ever considered those classes to be boring or pointless.

P.S. Thanks for the edit.

P.P.S.: I daresay the article / book “Hiroshima” would leave an impression on anyone, regardless of age. You could tell people it was a work of ficition and it would still have that effect. It ought to.

To komarov @#15

Part of the reason is, I think, that the war itself is not really covered as part of regular education. History classes received in two (EU) countries covered Nazi Germany right up to the start of the war and essentially stopped there. The same, incidentally goes for WWI, which was mentioned mostly as background for Hitler’s rise and the Russian revolutions. I guess this means the two biggest wars to shape Europe and the world in general don’t offer much in the way of valuable teaching material. They just form the backdrop to the Nazi Thing.*

Sounds like you were unlucky to get particularly bad education. For me (in Latvia) history lessons started with Homo erectus and ended with 1991 (the end of USSR). Of course, we did learn about Nazi Germany, but there was no particular emphasis on this topic. My only problem was the ideological bias. We were told mostly correct facts (OK, some important facts, like, Japan’s attempt to surrender, were skipped), but the interpretation was sometimes biased. USSR and German war atrocities were committed, because their leaders were evil and didn’t care about human lives. American/British/French/Latvian etc. war atrocities were committed, because they were necessary to end the war.

At first I didn’t question the bombing of Hiroshima, because (unless you know that Japan was already attempting to surrender) this fit perfectly with how all sides fought during WWII. Destruction of cities and killing of civilians was simply what every side did during WWII, it simply was an integral part of how this war was fought.

Just look at the Siege of Leningrad. It killed more than a million civilians. Slowly dying from starvation is a really nasty way how to die. Or look at how German cities were reduced to rubble with normal bombs, for example, the bombing of Dresden in World War II. And everybody was dropping bombs on cities. Fucking everybody. And, once the war was over, USSR soldiers simply gang raped millions of German (civilian) women. Those civilians who were lucky to survive air strikes had a pretty good chance of dying (or become scarred for life) after the war was already officially over.

Compared to other WWII atrocities, dropping nuclear bombs on cities sort of fit in. It barely stood out. This is exactly why, before learning the little fact that Japan was already attempting to surrender, I never paid much attention to the fact that nukes were used.

Some people have a tendency to claim that WWII was a giant battle between good and evil and the good side won. I disagree. Every damn side involved in this war was fucking evil. They all killed civilians, they all committed atrocities.

A little late, but I would like to offer some obligatory OMD :

[youtube https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d5XJ2GiR6Bo&w=560&h=315%5D

Sunday Afternoon@#18:

some obligatory OMD

Hm, it didn’t do much for me, except make me want to go brush up my nerd chic. Am I weird for having never heard of them?

Ieva Skrebele@#17:

Some people have a tendency to claim that WWII was a giant battle between good and evil and the good side won. I disagree. Every damn side involved in this war was fucking evil. They all killed civilians, they all committed atrocities.

That’s how I feel, too. I was raised with a solid anti-soviet indoctrination, but a bit of history and some thinking and your conclusion is unavoidable. Every damn side involved in this war was fucking evil.

Re: Ieva Skrebele (#17):

Sorry, I didn’t mean to imply those had been the only topics ever covered in my history classes. But the ‘recent history’ ended when the first shots of the second world war started, and essentially skipped over the first. Almost everything I do know about the wars themselves comes from books, documentaries and other sources but sadly was never part of any official curriculum of mine.

A fair assessment of both world wars, really. But I disagree with the nuclear attacks “barely standing out”. I won’t bother making my mind up as to which is worse, a protracted bombing campaign or a single death blow to a city. However, the US really went the extra mile on this one, developing new technology, new physics even, to be able to deal that single blow to a city. Even without a critical assessment whether the attacks were necessary, justified or whatever, that fact still sets them apart from conventional bombing.

Marcus @ #18:

If you grew up in the early ’80s in the UK as I did, I would answer “yes”, but you didn’t, so I think the answer is “no”.

I’m still struck by the incongruity of Enola Gay being a catchy little ditty (that has been an ear worm for the last day, yet again) and only a significant time later understanding the significance of the song.

komarov@#21:

I disagree with the nuclear attacks “barely standing out”. I won’t bother making my mind up as to which is worse, a protracted bombing campaign or a single death blow to a city. However, the US really went the extra mile on this one, developing new technology, new physics even, to be able to deal that single blow to a city.

The US really went the extra mile. The Manhattan Project was risibly expensive, setting the tone for the US’ trajectory of “death by military spending” – huge factory cities, reactors, power distribution, mining, transport; most of that was rolled up in other expenditures to hide them. For example the Tennessee Valley Authority’s push for hydroelectric power was, in part (maybe the large part) to power Oak Ridge. Something like 200,000 people participated in the Manhattan Project – most of them having no idea at all what they were doing. In terms of a total war economy, it was “not bad” because they could use labor that otherwise wouldn’t work at the front lines. On the flip side, the spend developed computers, teflon, aramid, advanced explosives, practical physics, high speed photography, and a whole bunch of other things.

I tried to call out why I believe nuclear weapons are memorably horrible: they are instantaneous (or have been, so far) and there’s nothing you can do; the destruction is total. You go from ‘fine’ to ‘dying’ in microseconds and everyone around you does too – we’re social animals and nuclear weapons instantly destroy civilization – there are no first responders, there are no shocked but intact survivors. When I read Vonnegut’s account of Dresden, that’s one of the things that jumps out at me: there are people who came through intact – that gives us the room to believe we might be one of them.

Of course, ballistic weapons raise the level of horribleness. I always wondered if “they” would tell us what was coming. Or would they just run for their bolt-holes and let us be surprised? At the height of the cold war, when Able Archer 83 happened, I was in college, and the big hitters would have come in on a polar trajectory, 30 minutes of silent waiting like a bug with the heel of a shoe descending on it; SS-20s clearing the northeast corridor. I wouldn’t have seen the outbound trails from the midwest silos – I might have been blithely doing my life when everything flashed to carbon.

I tried to call out why I believe nuclear weapons are memorably horrible: they are instantaneous (or have been, so far) and there’s nothing you can do; the destruction is total. You go from ‘fine’ to ‘dying’ in microseconds and everyone around you does too

That is a matter of opinion. Personally I would prefer an instant death rather than prolonged suffering. With conventional bombs people spend months living in horror and wondering whether they will survive. With nukes people have a perfectly normal life until they die in an instant. For a hedonist like me the second option sounds a lot more pleasant. If I was living in a city where bombs are regularly dropped my head and there was no option to flee this city, I would probably commit a suicide anyway. I believe that life is worth living only as long as I’m enjoying it.

there are people who came through intact – that gives us the room to believe we might be one of them.

Again, this is a matter of opinion. Some people (those who also tend to buy lottery tickets) are optimistic. I’m not. When I know that statistically majority of people end up dead or injured in a given situation, I always assume that I will end up dead on injured.

But I do find nukes a lot scarier than any other weapons. They make it possible to destroy all life on this planet. With normal bombs this would be impossible. Something somewhere would end up still alive. This planet is beautiful. I don’t like the idea that humans might destroy it.

Ieva Skrebele@#24:

That is a matter of opinion

That’s why I said “I believe…”