Timothy Garton Ash writes us a book about reviewing the Stasi – the East German secret police – file on himself. [amazon]

The mixed-up files of the stasi [source]

The sources the Stasi themselves considered most important were the “unofficial collaborators,” the IMs. The numbers are extraordinary. According to internal records, in 1988 – the last “normal” year of the GDR – the Ministry for State Security had more than 170,000 “unofficial collaborators.” Of these, some 110,000 were regular informers, while the others were involved in “conspiratorial” services such as lending their flats for secret meetings or were simply listed as reliable contacts. The ministry itself had over 90,000 full-time employees, of whom less than 5,000 were in the HVA foreign intelligence wing. Setting the total figure against the adult population in the same year, this means that about out of every fifty adult East Germans had a direct connection with the secret police. Allow just one dependent per person and you’re up to one in twenty-five. [Ash]

In the US, that level of coverage would take 6,000,000 people, plus or minus. But, in the US, our technology companies and the government have colluded to get everyone to carry a smart tracking device which they keep on them practically all the time. The US FBI only employs about 35,000 people with its annual budget of $8 billion, but it’s very hard to say what the police coverage of the US is, because there are state and local police of varying degrees of militarization, cooperating to various degrees with the FBI and eachother. There is, also, the US intelligence apparatus, with a $50 billion budget, which dwarfs the FBI (and tries to surveil everybody).

Ash gets his file and discovers it is surprisingly large. As a journalism student who travelled to/from the UK, and both Germanies, interviewing old state figures like Markus Wolf [wikipedia], he fit the profile of a spy fairly well. He reads other peoples’ analysis of his actions, then compares them to his diaries. He describes his meetings with some of the people who filed reports on him – and a pattern that becomes noticeable: denial at first, then an excuse, “I had to do it” or “they controlled my job, and if I didn’t report on you my career would have been ruined.” There’s a cautionary tale embedded in this story, and Ash doesn’t dance around about it – nor does he dwell on it: it is obvious enough.

When I tell people about my file they say strange things like “How lucky!” or “What a privilege!” If they themselves had anything to do with Eastern Europe, they say, “Yes, I must apply to see my file,” or “It seems that mine was destroyed,” or “Gauck tells me mine is probably in Moscow.” No one ever says, “I’m sure they didn’t have one on me.” One could describe the syndrome in Freudian terms: file envy.

Actually, mine is very modest compared with many. What is my single binder against the writer Jurgen Fuchs’ thirty? My 325 pages against the 40,000 devoted to the dissident singer Wolf Biermann? Yet small keys can open large doors. This is a way into much bigger rooms. Wherever there has been a secret police, not just in Germany, people often protest that their files are wholly unreliable, full of distortions and fabrications.

I find the emphasis on pages and binders to be quaint. Nowadays it’s just zones of ones and zeroes on heirarchical storage systems, somewhere. If and when the US police state falls, there will be no files – they’ll all vanish in cloud of bits and lies. There will be no journalists exposing which of their peers was reporting their actions, it will all be plausibly deniable.

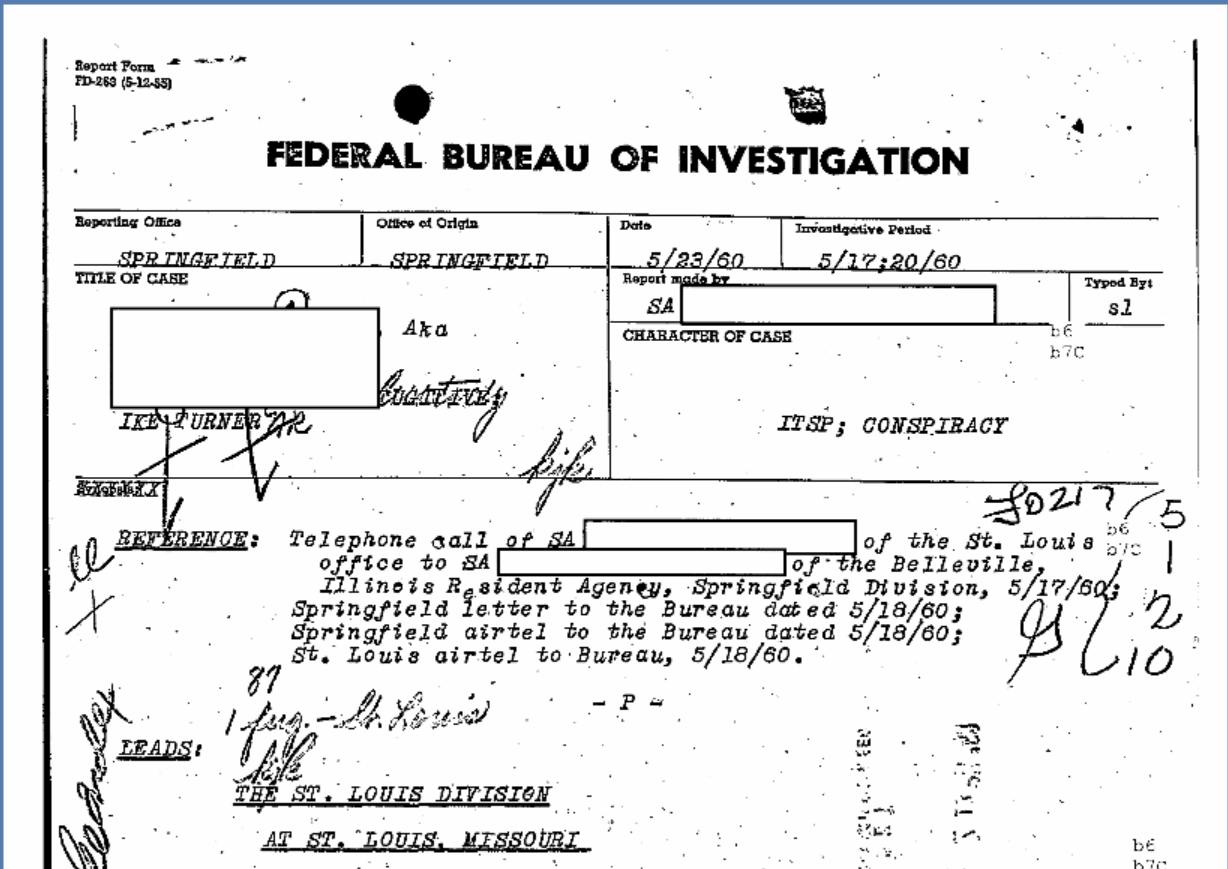

That’s a page from Ike Turner’s FBI file, which you can get on the internet thanks to a FOIA request. [turner] The FBI had 350 pages on him, but what’s creepiest is that they had special agents following him around all the time for a while, until they could conclude that he wasn’t likely to become an activist. The drugs and violence didn’t matter, it was the potential for activism that made them want a file full of dirt they could use to destroy him. The Stasi were looking for the same thing: just collect it all, because information might allow soft control.

As I race up the battered autobahn to Berlin, just as I used to all those years ago, I think back over this conversation: how a file opens a door to a vast sunken labyrinth of the forgotten past, but how, too, the very act of opening the door is like an archeologist letting in fresh air too a sealed Egyptian tomb.

For these are not simply past experiences rediscovered in their original state. Even without the fresh light from a new document or another’s recollection – the opened door – our memories decay or sharpen, mellow or sour, with the passage of time and the change of circumstances. Thus Frau Haufe, for example, surely had a different memory of “Michaela” in 1985, when the GDR still existed, than she did ten years later, on the eve of my visit. But with the fresh light the memory changes irrevocably. A door opens, but another closes. There is no way back now to your earlier memory of that person, that event. Or like a bad divorce, where today’s bitterness transforms all the shared past, completely, miserably, seemingly forever. Except that this bitter memory, too, will fade and change with the further passage of time.

Later:

A few months later I deliver a public lecture in Berlin on what to do about the communist past. I discuss, in some detail, the opening of the Stasi files. Among the people who come up to me afterward I am surprised to see “Smith.” He gives me an envelope. Opening it back at my hotel I find a letter stating that he has applied to see his file and that he would be glad to meet again “to consider individual points.”

Meanwhile he attaches a three-page typescript entitled “Some thoughts on the MfS.” This makes no mention at all of his own involvement but discusses the whole problem in general terms, as one interested scholar writing to another. For example: “The material in MfS files reflects the self-image of the MfS (manner of reporting, interpretation, terminology, etc.). Anyone conversant with text analysis and the problems of perception and objectives in creating texts will appreciate the care that is needed in interpreting material of this kind.”

The word “I” does not appear once in his text.

Keeping up with the modern times, the Stasi files are now available online. [stasi]

The reason we dwell on these things is not to torture ourselves, but to remember why we later concluded they were a bad idea. The Europeans have extensive experience with how bad police states can get. Watching the world’s greatest superpower slowly slide under the control of a surveillance bureaucracy has to be both scary and familiar.

Of course, in the US, much of the work is contracted out, making it even more difficult to get any idea of of how many people are involved…

On the subject of the surveillance of artists, here’s a hilarious routine from Arlo Guthrie in which he credits his entire career to the various local, state, and federal agencies who sent undercover people to his early gigs: Arlo Guthrie Thanks the Narcs.

Dunc@#1:

Of course, in the US, much of the work is contracted out, making it even more difficult to get any idea of of how many people are involved…

Yup. By the way, the word we need to start using is ‘collaborators.’ Not ‘contractors.’

Arlo Guthrie Thanks the Narcs.

OMG! I still remember the glossy 8×10 photos with the circles and arrows!!! I didn’t realize Guthrie was still riding that train. I’ll check it out.

I didn’t watch the youtube, so this may have already been covered, but I saw an Arlo Guthrie concert and he talked about getting his FBI file. All his friends had big fat files full of lots of pages. He was jealous when he got his and it only contained the words to “Coming into Los Angeles”. Which he launched right into.

Just thinking a bit more about some of the stuff that Arlo is saying there… [dons tinfoil hat] Is it just a co-incidence that marijuana legalisation is finally getting traction now that the state has other, far more effective means and excuses for mass surveillance?

Dunc@#4:

Wow, that’s some tinfoil hat think!!

I … dunno. They still need an excuse to shove you into the underclass if you’re not muslim.