The Japanese space agency sent a probe, Hayabusa 2, to an asteroid that returned with physical samples from its surface. The samples are being scrutinized closely in a search for signs of microscopic life — they have found plenty of organic molecules, as was expected from a chondrite.

They did find some suggestive shapes, tiny rods and cylinders, that have dimensions in the ballpark of what we see in terrestrial life. Maybe these are examples of extraterrestrial organisms crawling over the surface of space rocks? Maybe?

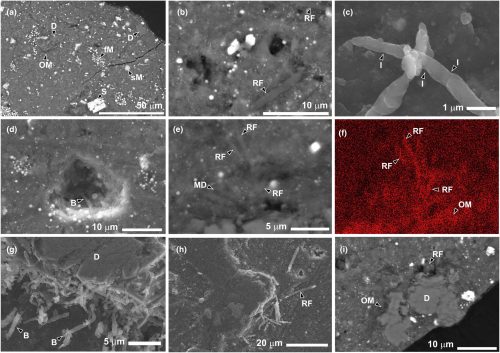

Electron microscope images of sample A0180. (a) A backscattered electron image (BEI) showing a matrix dominated by phyllosilicate with framboidal (fM) and spheroidal (sM) magnetite, dolomite (D), and sulfide (S). Areas containing abundant organic matter (OM) are present. (b) A BEI of rods and filaments (RF) on the surface of the specimen. (c) A secondary electron image (SEI) showing the detailed morphology of filaments with indents denoting individual cells. (d) A SEI of the cavity shown containing an organic rod structure. (e) A BEI showing cluster of rods and filaments around a dolomite grain. A cylindrical mold (MD) is also present. (f) A carbon Kα map of the image shown in e illustrating that filaments are carbon-rich (RF) and showing a C-rich rim on the dolomite grain. The contrast of the map has been enhanced using a linear filter. All pixels with an intensity of >50% are saturated (g) A secondary electron image showing highly elongate filaments. (i) A BEI of a dolomite grain surrounded by matrix containing abundant organic matter. A cluster of filaments is also present. Images were obtained on the November 11, 2022 (a–d), November 30, 2022 (g, h), and the January 14, 2023 (e, f).

Except…no, the observations are more compatible with the idea that the organic molecules on the rock are suitable fuel for the growth of earthly contamination.

The presence of microorganisms within meteorites has been used as evidence for extraterrestrial life, however, the potential for terrestrial contamination makes their interpretation highly controversial. Here, we report the discovery of rods and filaments of organic matter, which are interpreted as filamentous microorganisms, on a space-returned sample from 162173 Ryugu recovered by the Hayabusa 2 mission. The observed carbonaceous filaments have sizes and morphologies consistent with microorganisms and are spatially associated with indigenous organic matter. The abundance of filaments changed with time and suggests the growth and decline of a prokaryote population with a generation time of 5.2 days. The population statistics indicate an extant microbial community originating through terrestrial contamination. The discovery emphasizes that terrestrial biota can rapidly colonize extraterrestrial specimens even given contamination control precautions. The colonization of a space-returned sample emphasizes that extraterrestrial organic matter can provide a suitable source of metabolic energy for heterotrophic organisms on Earth and other planets.

The paper gives a detailed timeline of how the sample was treated, from the moment of collection with sterilized instruments in space to all the cutting and polishing they needed to do to expose a ‘clean’ surface, and examination with various instruments. It turns out that you can store it for long periods of time in extremely low pressure chambers or pure nitrogen gas, but at some point you’re going to have to expose it to our atmosphere so you can cut it and embed in epoxy and grind and polish it, and that’s an opportunity for contamination. The authors think that’s what happened.

The change in the population of microorganisms over the course of 64 days suggests the sample was contaminated with microorganisms during the preparation of the polished block. Indeed, the sterile handling and storage under which the sample was kept from its return to Earth (Yada et al., 2022) until it was removed from a nitrogen atmosphere, immediately prior to XCT analyses, makes it highly unlikely it was contaminated prior to sample preparation. The possibility that the sample contained indigenous spores is also unlikely since only a small number of microorganisms were initially present despite the 280 days it had spent at ambient temperature since the return of Hayabusa 2.

I can’t call this a disappointing result because, after reading the protocols and the unavoidable exposure to our filthy, dirty planet, I think this should have been an expected result. I am impressed with how avidly our bacteria will leap into action to gnaw on even a dead rock containing organic carbon.

I associate “Hayabusa” with crotch-rockets on the Autobahn videos so this was different from what i expected…

Hayabusa means peregrine falcon in Japanese, so it’s no surprise it’s been used for both spacecraft and motorcycles. It was also the name of the Nakajima Ki43 fighter, the primary single engine fighter of the Imperial Japanese Army Air Force in WW2. (The more famous Mitsubishi Zero was a Navy aircraft.)

I saw an article the other day on speculations that the experiments on the original Viking probe many have killed any life that was sampled. But the author also seemed to be implying that Viking might have killed all life on Mars.

My God, have we learned nothing from “Species?” Or “Species 2?”

I have learned that if I spot Natasha Henstridge naked and eyeing me lasciviously that I need to run away.

This doesn’t sound right. I think we need to have Avi Loeb look at the data and see if there are any advanced civilizations on 162173 Ryugu.

Avi Loeb is secretly an alien agent sent to Earth to discredit signs of intelligent life elsewhere by making increasingly eye rolling claims.

Terrestrial bacteria have had 4 billion years of competition with other hungry organisms to hone their ability to glom onto resources quickly and efficiently, lest some other bacteria get there first or out-compete them. Even if there were space-borne organisms on the cometary rocks, I would expect them to quickly succumb to our superior scum.

@PZ, # 4: Species had a lot of bad science, but a couple good insights into human behavior:

“I would never hurt you.”

“Yes you would. You just don’t know it yet.”

Well, keeping the material in inert atmosphere sounds quite proper, but a colleague of mine kept some (different, metallic) samples in a vacuum chamber, and they got oxidised anyway. Oxygen gets around aggressively, and longer times embiggen the odds.

Further: embedding, grinding and polishing are filthy processes. Show me someone who claims to do it all nice and clean-like and I’ll show you a liar – it’s a nightmare.

So contamination is very likely, I’m afraid.

This said… a wonderful opportunity that was, working on extra-terrestrial materials no less! I would have liked to be there myself.

Has no one learned anything from The Andromeda Strain”?

@2. timgueguen : “I saw an article the other day on speculations that the experiments on the original Viking probe many have killed any life that was sampled. But the author also seemed to be implying that Viking might have killed all life on Mars.”

This article in space dot com? :

Plus :

Source : https://www.space.com/space-exploration/search-for-life/did-nasas-viking-landers-accidentally-kill-life-on-mars-why-one-scientist-thinks-so

The article continues with an interview in which Dirk Schulze-Makuch goes into much more depth and discusses this view. I didn’t see anything suggesting the Vikings killed all life on Mars there though.

StevoR, I just copypasted and searched (select, right-click, hit search):

https://www.popularmechanics.com/space/moon-mars/a62942369/mars-lander-killed-life/

TL;DR: the lander may have killed whatever life it was looking for and so did not find any.

(As per timgueguen’s summary)

@ ^ John Morales : Ah. Okay, thanks.

@ ^Although.. hmm.. having read it I don’t think the article actually killed ALL life on Mars although I guess you could stretch it to maybe implying that if you metaphorically squint hard enough..

I definitley agre ewith the final paragrpah there.